Table of contents

Deferred revenue

Founders get surprised when cash in the bank and "revenue" move in opposite directions. Deferred revenue is usually the missing explanation—and it affects how confident you should be in your forecast, your renewal risk, and how aggressively you can spend.

Deferred revenue is the amount you've billed (and often collected) for subscription service you have not yet delivered, so you cannot recognize it as revenue yet. It sits on your balance sheet as a liability because you "owe" future service.

What deferred revenue tells you

Deferred revenue answers a practical question: how much already-billed revenue is "in the tank" but not yet earned.

It's most useful for founders because it sits at the intersection of three realities:

- Billing strategy (cash timing): monthly vs annual upfront, multi-year contracts, payment terms.

- Revenue recognition (financial reporting): when you can record revenue under your policy (typically straight-line for subscriptions).

- Delivery and churn risk: if customers cancel, downgrade, or demand refunds, some deferred revenue may never turn into revenue.

How it differs from "growth" metrics

Deferred revenue is not a growth metric by itself. It can rise even if your product momentum is flat—simply because you pushed more customers to annual prepay or sold longer terms.

It also doesn't replace core subscription metrics like MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) or ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue). Those describe run-rate. Deferred revenue describes unearned billed amounts sitting on the balance sheet.

Current vs noncurrent matters

Most accounting systems split deferred revenue into:

- Current deferred revenue: expected to be recognized within the next 12 months.

- Noncurrent deferred revenue: expected to be recognized after 12 months (common with multi-year contracts).

For planning, this split matters because it changes how much "near-term recognition" you should expect even if total deferred revenue is large.

The Founder's perspective

If you're debating whether to hire 2 more reps or 2 more engineers, deferred revenue helps you sanity-check confidence in near-term revenue recognition. A big balance that is mostly noncurrent doesn't protect next quarter the way current deferred revenue does.

What drives deferred revenue

Deferred revenue moves for a handful of operational reasons. If you can't explain the change in one sentence, you likely have a data hygiene or policy problem.

It increases when you bill ahead of service

Common drivers:

- Annual or multi-year prepay (biggest driver in most SaaS)

- Upfront invoices for renewals issued before the renewal start date

- Expansion billed in advance (e.g., adding seats for the next contract period)

- Implementation or onboarding fees if you treat them as services delivered over time (policy-dependent)

Discounting changes the size of the bill but not the basic mechanism. If you use annual discounts, make sure you understand how Discounts in SaaS affect both cash and recognition.

It decreases when you earn revenue or reverse the obligation

Deferred revenue goes down when:

- You recognize revenue as time passes (see Recognized Revenue)

- You refund unearned amounts (see Refunds in SaaS)

- You issue credits that reduce future service obligations

- There's a contract modification (downgrade, early termination) that reduces remaining obligation

Invoice timing and payment terms can distort it

Two common distortions:

- Invoice issued, not yet paid: Depending on your setup, this can create deferred revenue alongside accounts receivable. That's why deferred revenue often needs to be read together with Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging.

- Mid-month start dates: Annual prepay doesn't always mean "12 equal months left" at period end. If many customers start late in the month, your deferred revenue may be higher than a simple average would suggest.

How to calculate deferred revenue

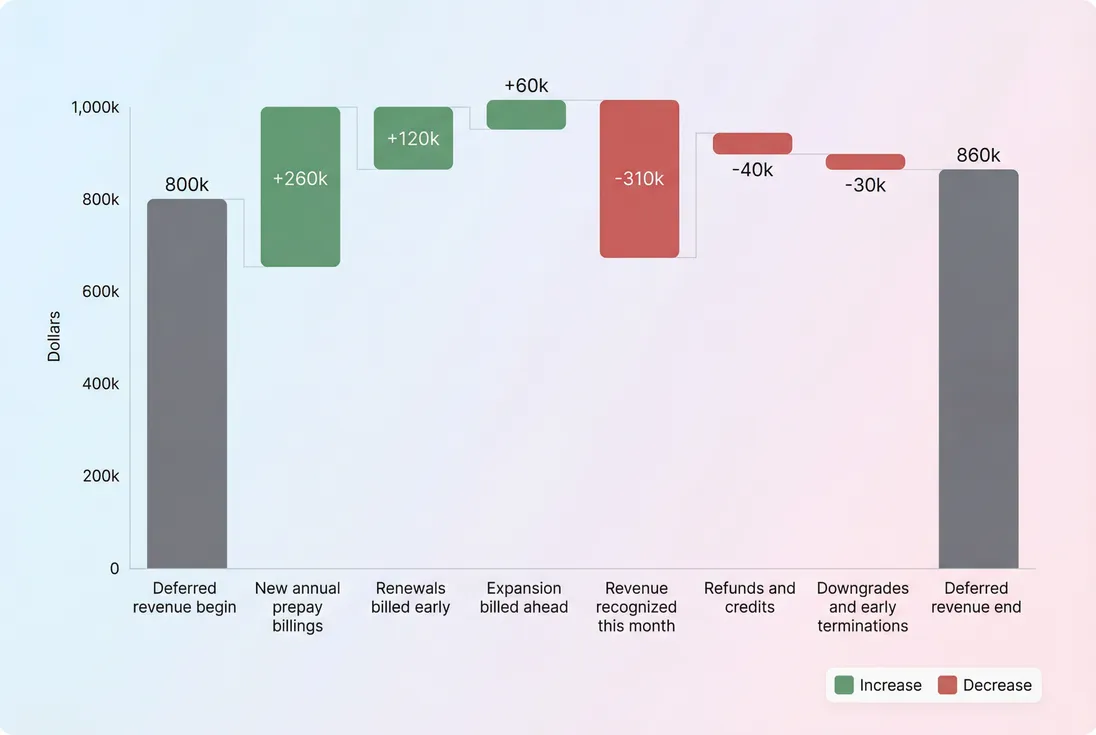

At its core, deferred revenue is a roll-forward: beginning balance plus new deferrals minus recognized portions (and any reversals like refunds).

In plain English: you add what you billed for future delivery, and subtract what you earned (and what you gave back).

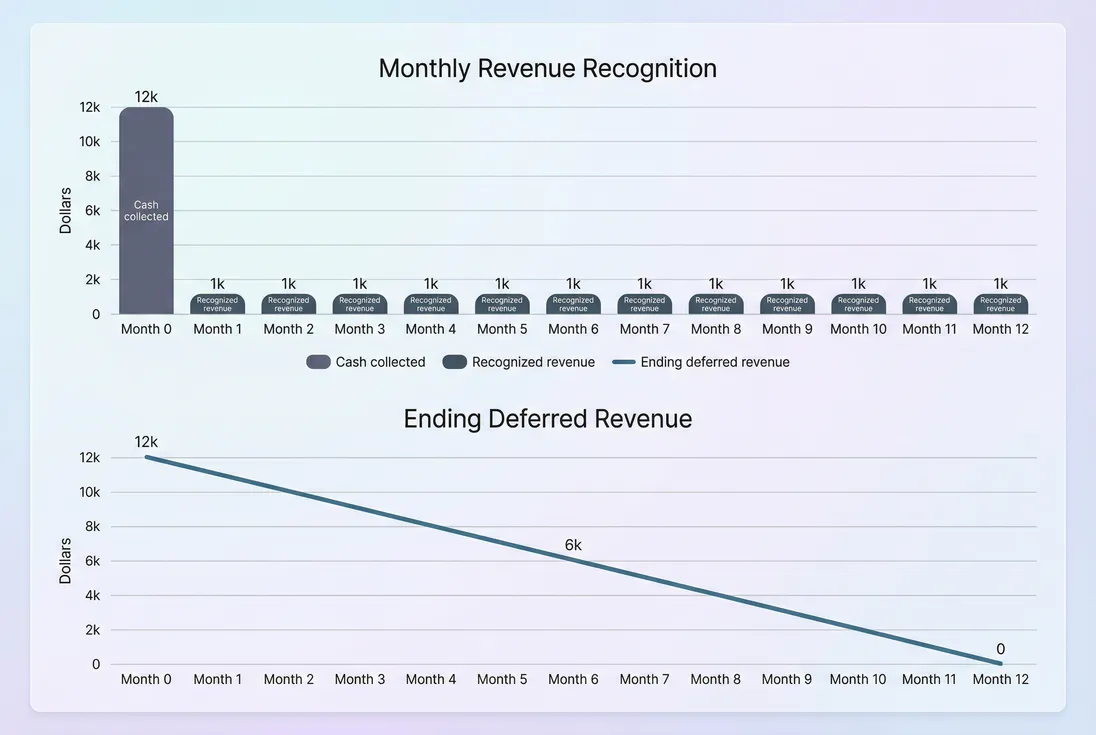

A concrete example (annual upfront)

Customer pays $12,000 on January 1 for 12 months.

- Day 1: cash increases by $12,000, deferred revenue increases by $12,000

- Each month: recognize $1,000 revenue; deferred revenue drops by $1,000

- By month 6 end: deferred revenue is $6,000

- By month 12 end: deferred revenue is $0 (assuming no renewal yet)

This is why founders who push annual prepay often see cash improve immediately while revenue ramps in over time.

A useful derived metric: deferred revenue coverage

Founders often want a quick "how many months of already-billed revenue do we have?" view. A simple approximation:

This is not GAAP and won't be perfect (mix of services, one-time items, seasonality), but it's a practical planning lens.

- Coverage rises: you're billing further ahead, or recognition slowed.

- Coverage falls: you're billing less ahead, recognition sped up, or refunds/terminations increased.

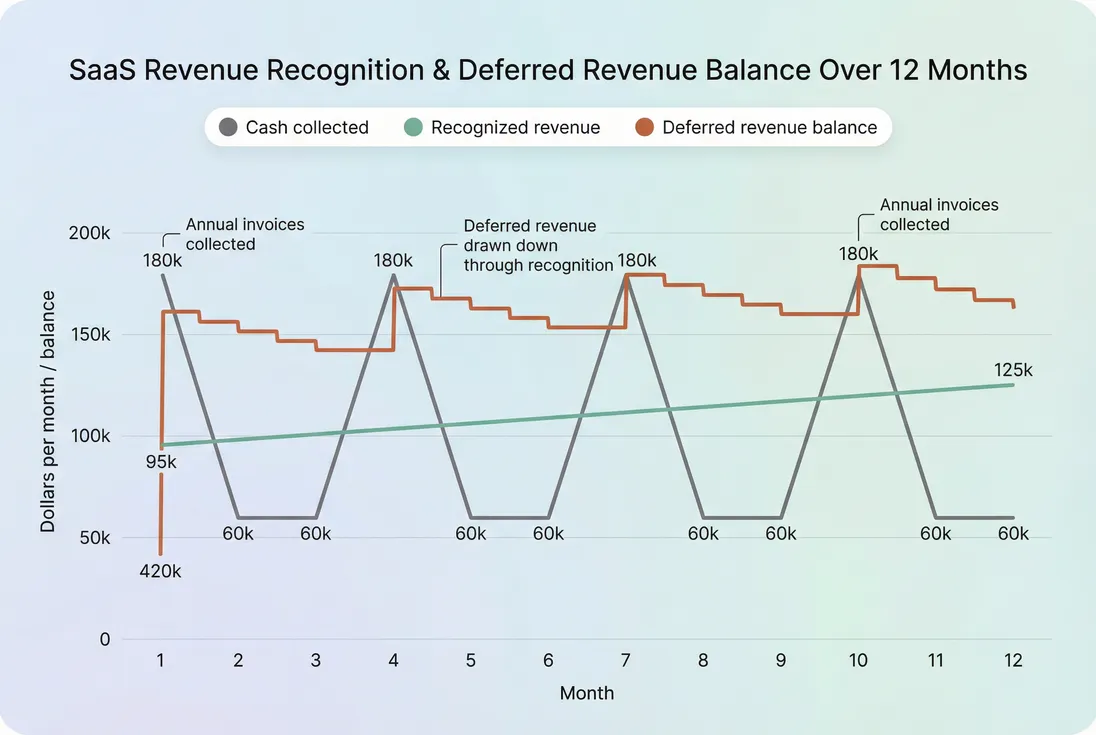

How to interpret changes month to month

The biggest mistake founders make is celebrating an increase (or panicking over a decrease) without asking: did our billing terms change, or did our business change?

A clean way to interpret change is to decompose it.

What an increase usually means

Most common explanations (in order of frequency):

- More customers paying annually (or multi-year) rather than monthly

- Higher volumes of renewals billed before the service period starts

- More expansion captured as prepaid commitments

- Slower revenue recognition due to delivery delays (often a red flag)

Here's the founder-level interpretation:

- If deferred revenue rises because annual prepay mix improved, that's usually good for cash and reduces financing pressure.

- If it rises because recognition slowed, investigate operational causes (implementation backlog, go-live delays, disputes). That can create churn risk later.

What a decrease usually means

Common explanations:

- Renewal seasonality: you recognized revenue from last quarter's annual invoices, but haven't billed the next renewal wave yet.

- Shift toward monthly billing: customers resist annual; sales team discounts less; self-serve dominates.

- Higher churn or downgrades: obligations shrink through cancellations and credits.

- Recognition catch-up: you cleared previously deferred services (good if it reflects delivery; bad if it's policy noise).

Decreases are not automatically bad. If you intentionally stopped pushing annual prepay (to reduce discounting or improve conversion), you should expect deferred revenue to fall even if ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and retention are strong.

A quick diagnostic table

| What you see | Likely cause | What to check next | Common decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deferred revenue up, cash up, MRR steady | More annual prepay | Mix of annual vs monthly, discount rates | Decide if annual incentive is worth it |

| Deferred revenue down, MRR up | Billing less ahead | Payment terms, self-serve share | Improve collections, consider annual upsell |

| Deferred revenue down, cash down | Demand or retention issue | churn, renewals, refunds | Tighten spend; fix retention |

| Deferred revenue up, MRR down | Timing/policy mismatch | invoicing schedules, credits | Audit revenue recognition and credit logic |

The Founder's perspective

When deferred revenue falls at the same time pipeline "looks fine," I assume renewal execution is the issue until proven otherwise. It's a forcing function: either customers aren't renewing, or you're not getting them to commit upfront.

How founders use it in planning

Deferred revenue becomes powerful when you connect it to operating decisions: hiring pace, discounting, and customer success capacity.

Revenue forecast sanity check

If your forecast assumes steady recognized revenue growth, but deferred revenue is shrinking and annual renewals are weak, you're implicitly betting on near-term bookings to fill the gap.

This is where deferred revenue complements run-rate metrics like CMRR (Committed Monthly Recurring Revenue). CMRR is about committed subscription run-rate; deferred revenue is about already-billed obligations.

A practical founder workflow:

- Forecast recognized subscription revenue next quarter based on current customer base.

- Compare to current deferred revenue expected to recognize next quarter.

- If there's a gap, you need either:

- more billings (bookings), or

- a billing cadence shift (annual incentives), or

- acceptance that revenue will slow.

Cash planning and runway

Deferred revenue is not cash, but it is often correlated with cash because it usually comes from invoicing and collections.

Use it alongside:

- Burn Rate and Runway (how long your cash lasts)

- AR health via Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging (how much billed cash you haven't collected yet)

A company can look "safe" on deferred revenue while still facing cash pressure if AR is expanding (slow-paying enterprise customers).

Pricing and term-length strategy

Deferred revenue is one of the quickest ways to see if your billing strategy is working:

- If you introduce "2 months free on annual" and deferred revenue rises sharply, you improved upfront commitments—but you may have increased discounting.

- If you remove the discount and deferred revenue falls, you may have improved unit economics but weakened cash timing.

Tie this back to ASP (Average Selling Price) and longer-term efficiency metrics like CAC Payback Period. Annual prepay can shorten payback dramatically even if recognized revenue doesn't change.

Tax and VAT considerations

If you sell internationally, taxes can complicate "cash collected" versus "revenue recognized." For example, VAT may be collected and remitted, and should not inflate revenue. Make sure your billing and accounting treatment is consistent (see VAT handling for SaaS).

When deferred revenue misleads you

Deferred revenue is simple in concept, but messy in real systems. These are the traps that cause founders to make the wrong call.

Mixing one-time and recurring items

One-time charges can create deferred revenue if they represent undelivered service, but many one-time charges are recognized immediately (or on completion). If you lump everything together, deferred revenue "coverage" will swing for reasons unrelated to retention.

If you have significant non-recurring charges, separate analysis using One Time Payments.

Usage-based pricing edge cases

In Usage-Based Pricing, revenue is often recognized after usage happens. That can create:

- Unbilled receivables (usage happened, not yet invoiced)

- Less classic "prepaid deferred revenue" unless you collect credits up front

So a usage-heavy business might have low deferred revenue even with strong growth. Don't misread that as weak demand.

Refunds, credits, and disputes

Refunds and credits are operational signals, not just accounting entries. If deferred revenue drops due to credits:

- it can indicate onboarding failures,

- poor expectation setting,

- or customer success overload.

If you see credits rising, pair the analysis with Churn Reason Analysis and retention metrics like GRR (Gross Revenue Retention).

Policy changes that break comparability

If you change revenue recognition policy (or how you treat implementation services), deferred revenue trend lines can "jump" without any real business change. When you see a discontinuity, annotate it and avoid using that period for trend-based decisions.

Practical operating rules

If you want deferred revenue to drive better decisions (not just better reporting), use these rules.

- Always explain the delta. Every month, attribute the change to 3–6 drivers (new prepay, renewals billed, recognition, refunds/credits).

- Track mix explicitly. If annual prepay percentage changes, deferred revenue will change even if demand is flat.

- Pair it with AR. Deferred revenue without AR context can hide collections problems.

- Separate "good" from "bad" increases. Good: more prepaid commitments. Bad: recognition slowed because delivery is stuck.

- Don't treat it as a goal. Deferred revenue is a byproduct of terms and delivery, not a scoreboard.

The Founder's perspective

I use deferred revenue as a confidence gauge. If we're about to increase burn (new hires, bigger campaigns), I want to see either rising deferred revenue from real prepay commitments or clear evidence that renewals are locked. Otherwise, you're betting the company on future bookings.

Key takeaways

- Deferred revenue is billed (and often collected) cash for service you still owe, recorded as a liability.

- It rises mainly from annual or multi-year prepay and falls mainly from revenue recognition (and refunds/credits).

- The most actionable view is the roll-forward: what increased it, what decreased it, and why.

- Use it to sanity-check forecasts, term strategy, and cash planning—especially alongside AR, burn, and retention.

Frequently asked questions

Not always. Higher deferred revenue often means more upfront billing, larger renewals, or longer contracts, which is good for cash and visibility. But it can also rise from heavy discounting to pull cash forward or from implementation delays that slow recognition. You need to tie changes to billing terms and delivery.

There is no universal benchmark because deferred revenue depends on billing cadence. A monthly-only SaaS may have very little. A SaaS with mostly annual prepay commonly carries several months of revenue in deferred revenue. Track it as coverage in months and monitor trend versus renewals and new bookings.

If you refund an unearned portion of a subscription, deferred revenue should decrease because you no longer owe service and no longer hold the cash. Chargebacks can create similar effects, plus payment disputes. Operationally, frequent refunds can make deferred revenue look volatile and can mask retention problems if you only watch MRR.

MRR and ARR describe contracted recurring revenue run-rate, while deferred revenue is a balance sheet liability representing service owed from cash already billed and collected (or invoiced). Annual prepay can increase deferred revenue without changing MRR. A shift from annual to monthly can reduce deferred revenue even if MRR stays flat.

First, separate normal seasonality from a real demand issue. Drops often come from fewer annual renewals, a move to monthly billing, higher churn, or a one-time recognition catch-up. Validate with renewal rate, new bookings, and invoice timing, plus audit refund activity and any revenue recognition policy changes.