Table of contents

CPL (cost per lead)

If you're "improving" CPL but growth is slowing, you're probably optimizing the wrong part of the funnel. CPL is easy to move with targeting tweaks and lead-form changes—but unless those leads turn into customers efficiently, a low CPL can quietly raise your true acquisition cost and waste sales capacity.

CPL (cost per lead) is the average amount you spend to generate one lead in a given channel, campaign, or time period.

What CPL reveals (and what it doesn't)

CPL is an upstream efficiency metric. It's most useful for answering: how expensive is it to create sales/activation "inputs" at the top of the funnel? That matters because lead volume and lead cost are the earliest signals that your go-to-market motion is scaling—or stalling.

But CPL is not a profitability metric. It says nothing about:

- Lead quality (do they become customers?)

- Unit economics (does the revenue justify the cost?)

- Sales capacity constraints (can your team work the volume?)

A founder should treat CPL as a diagnostic metric, not a scoreboard.

The Founder's perspective

If you're cash-constrained, CPL helps you detect efficiency regressions early (auction prices, creative fatigue, landing page breakage). But you should only "optimize CPL" when you can prove it improves downstream conversion or lowers CAC—not when it just creates more low-intent names.

Define "lead" before you optimize

Most CPL confusion comes from teams mixing different lead definitions.

Common "lead" types in SaaS:

- Inquiry lead: filled a form, requested a demo, downloaded a guide.

- Signup lead: created an account or started a trial.

- MQL: met a marketing qualification rule (fit + behavior). See MQL (Marketing Qualified Lead).

- SQL: accepted by sales as worth working. See SQL (Sales Qualified Lead).

These behave very differently. For example, an ebook lead might be $20 CPL and convert at 0.3%, while a demo-request lead might be $250 CPL and convert at 6%. The "better" channel depends on your ACV, sales cycle, and sales capacity.

Rule: Only compare CPL across channels if the lead definition is the same.

How to calculate CPL (the practical way)

At its simplest:

What counts as "total lead acquisition cost"

Include costs required to create the lead:

- Media spend (search, social, sponsorships)

- Agency fees or contractor costs tied to that program

- Creative production directly for that channel/campaign

- Marketing tools only if they're specific and incremental (otherwise treat as overhead)

- A reasonable payroll allocation if you want "fully loaded" CPL (be consistent)

What to exclude (unless you're explicitly measuring a later-stage metric like cost per SQL):

- Sales payroll (SDR/AE)

- Customer success

- Product engineering

- General brand spend that can't be attributed (unless you're using a blended CPL on purpose)

Pick a time window that matches reality

CPL looks "clean" in-week, but many channels have lag:

- Webinar leads may convert to SQL over 2–6 weeks

- SEO content may produce leads for months

- Retargeting may cannibalize conversions from other channels

If you're using CPL to make budget decisions, evaluate it on a window that captures the lead flow reliably (often weekly for ops, monthly for allocation).

CPL is upstream; it becomes meaningful when you translate it through conversion rates into implied CAC and revenue impact.

How CPL connects to CAC and payback

Founders often ask: "If my CPL is $X, is that good?" The only defensible answer is: it depends on what a lead becomes.

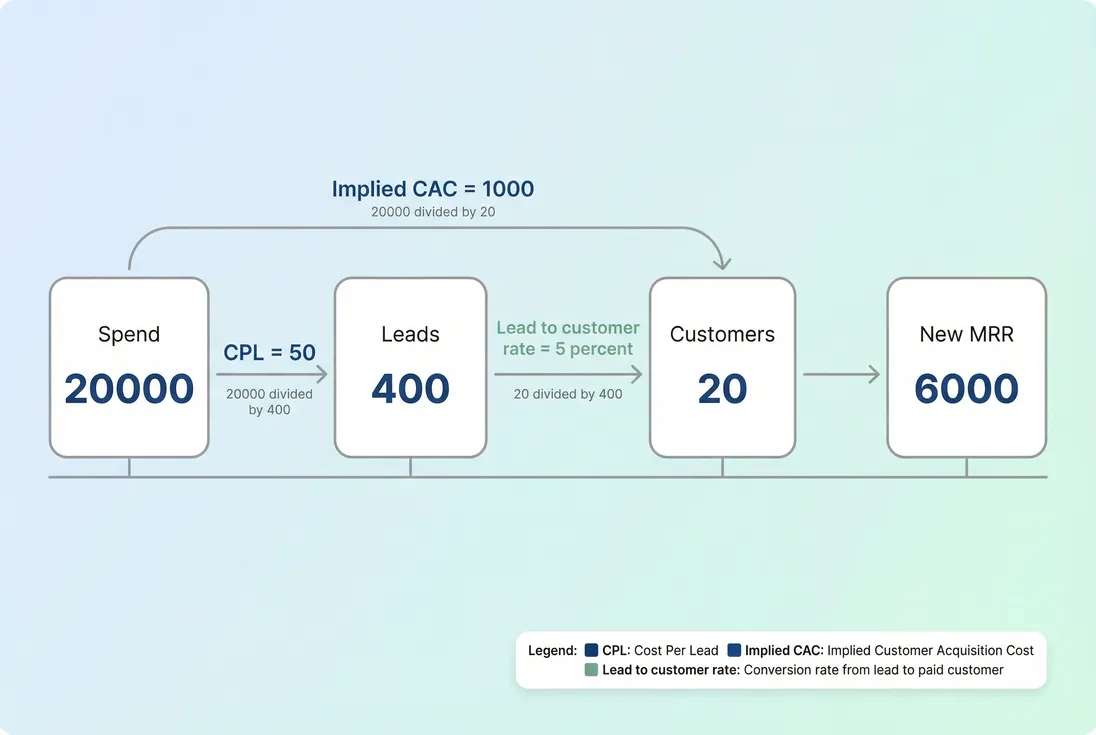

If you know your lead-to-customer rate (see Lead-to-Customer Rate), you can translate CPL into implied CAC:

Example:

- CPL = $50

- Lead-to-customer rate = 5% (0.05)

Implied CAC = $50 / 0.05 = $1,000

That CAC is only "good" if it supports your payback and LTV goals. To evaluate that:

- Compare to LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and LTV:CAC Ratio

- Compare to CAC Payback Period

- Sanity check against Burn Rate and Burn Multiple if you're scaling spend faster than revenue

Back into a maximum CPL (a founder-friendly guardrail)

If you have a target CAC and know your conversion rate, you can compute a ceiling:

Concrete scenario (B2B sales-led):

- Target CAC: $6,000 (based on payback constraints)

- Lead-to-customer rate from this channel: 2% (0.02)

Max CPL = $6,000 × 0.02 = $120

Above $120, you're likely buying growth that breaks your payback model unless something else improves (pricing, win rate, sales cycle, retention).

For conversion inputs, also review Conversion Rate and Win Rate.

The Founder's perspective

A CPL target is not a guess. It's derived from what you can afford (CAC/payback) and what your funnel actually converts (lead-to-customer). This makes budget conversations easier: you're not debating opinions, you're debating inputs you can change.

What drives CPL up or down

CPL is influenced by two big forces: traffic economics and conversion mechanics.

Traffic economics (what you pay for attention)

- CPM/CPC inflation: auctions get crowded, competitors raise bids, seasonality spikes.

- Targeting constraints: narrow ICP targeting raises cost; broader targeting lowers CPL but often lowers quality.

- Channel mix shifts: e.g., shifting from high-intent search to broad social often lowers CPL while hurting conversion downstream.

Conversion mechanics (what fraction becomes a lead)

- Offer strength: demo request vs webinar vs template download will change both conversion rate and lead intent.

- Landing page conversion rate: message match, proof, friction, load speed.

- Form friction: fewer fields usually lowers CPL, but can increase junk.

- Creative fatigue: CTR drops → CPC rises → CPL rises.

- Tracking quality: broken pixels, misfiring events, duplicate leads can create phantom "improvements."

A useful decomposition mindset is:

You don't need perfect attribution to use this. If CPL jumps 30% week-over-week, you can quickly check: did CPC rise, or did the page stop converting?

How to interpret CPL changes

CPL is only actionable when you interpret it alongside volume and down-funnel conversion.

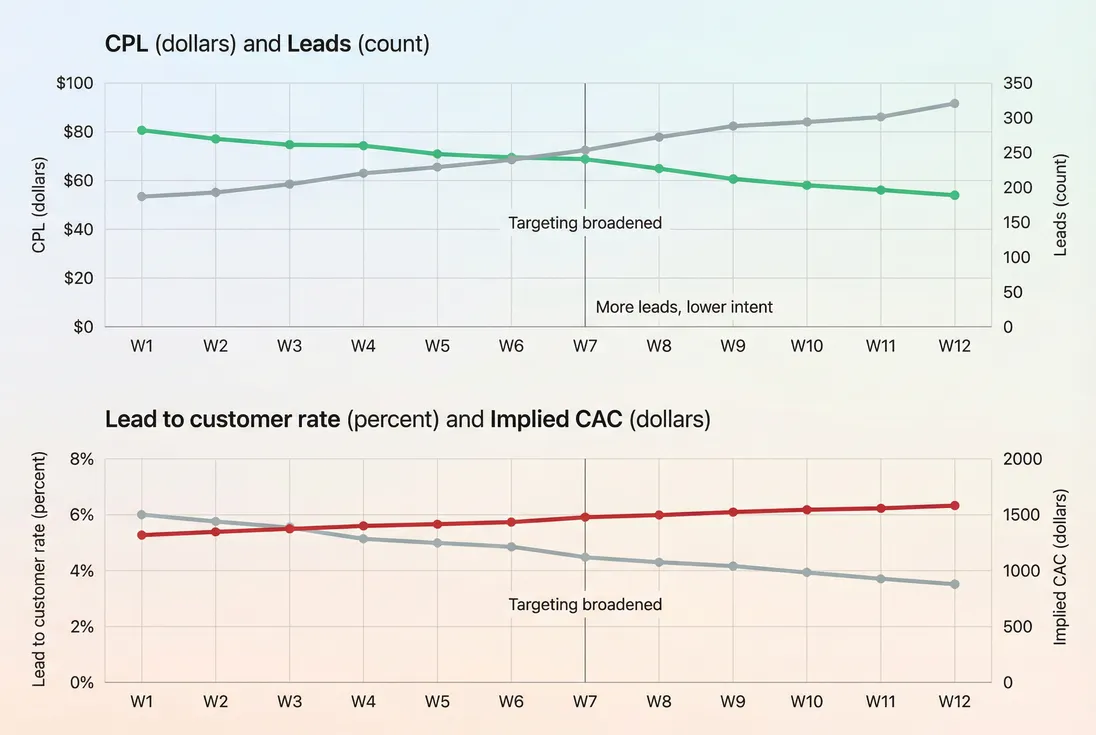

The classic trap: CPL improves, CAC worsens

This happens when you reduce friction or broaden targeting: you get more leads cheaply, but they convert poorly.

Track CPL with lead volume and lead-to-customer rate; otherwise you can "win" on CPL while losing on CAC.

A quick diagnostic table

Use this to interpret what likely changed and what to do next.

| What you see | Likely cause | What to check | Typical action |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPL up, leads flat | CPC/CPM inflation | Auction metrics, CTR | Refresh creative, tighten ICP, shift budget |

| CPL up, leads down | Conversion drop | Landing page CVR, form errors | Fix page, improve message match, reduce friction carefully |

| CPL down, leads up, CAC up | Lower lead quality | Lead-to-customer, SQL rate | Re-tighten targeting, change offer, add qualification |

| CPL down, leads down | Reduced spend or reach | Budget caps, frequency | Decide if volume loss is acceptable |

| CPL volatile day-to-day | Low volume or tracking | Lead dedupe, attribution window | Use weekly rollups, enforce definitions |

How founders use CPL for real decisions

CPL becomes a decision tool when you use it to answer four operational questions: Where do I spend next? What do I fix? What do I pause? What do I scale?

1) Budget allocation across channels

If you only rank channels by CPL, you'll often overfund low-intent sources. A better approach is to compare channels using:

- CPL

- Lead-to-customer rate (or cost per SQL if you're sales-led)

- Expected revenue per customer (use ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) or ASP (Average Selling Price))

A practical "channel scorecard" is:

- Implied CAC (from CPL and conversion)

- Payback estimate (CAC vs gross profit per month)

- Capacity fit (does sales have time to work this?)

2) Deciding whether to gate or ungate

Gating content (forms) increases "leads" and lowers CPL, but can reduce intent and waste SDR time. Ungating reduces leads but increases signal quality via behavior.

A founder-friendly test:

- Run gated and ungated versions for 2–4 weeks.

- Measure not just CPL, but SQL rate and win rate.

- If SQL rate drops materially, lower CPL is not a win.

This is especially important in Product-Led Growth motions where product usage signals are often more predictive than form fills.

3) Choosing offers and CTAs

Different CTAs create different lead economics:

- Demo request: higher CPL, higher intent, shorter path to opportunity

- Trial/signup: can be low CPL, but quality depends on onboarding and activation (see Product activation and Time to Value (TTV))

- Webinar/guide: low CPL, slower conversion, often needs nurture

Match the offer to your Go To Market Strategy and sales cycle realities.

4) Scaling spend without breaking economics

As you increase budget, CPL often rises due to audience saturation. Plan for this by:

- Setting a CPL guardrail (max CPL) per channel

- Scaling in increments and measuring down-funnel weekly

- Watching for creative fatigue and frequency

If you're sales-led (Sales-Led Growth), also watch your SDR/AE throughput so you don't "buy" more leads than you can follow up on quickly.

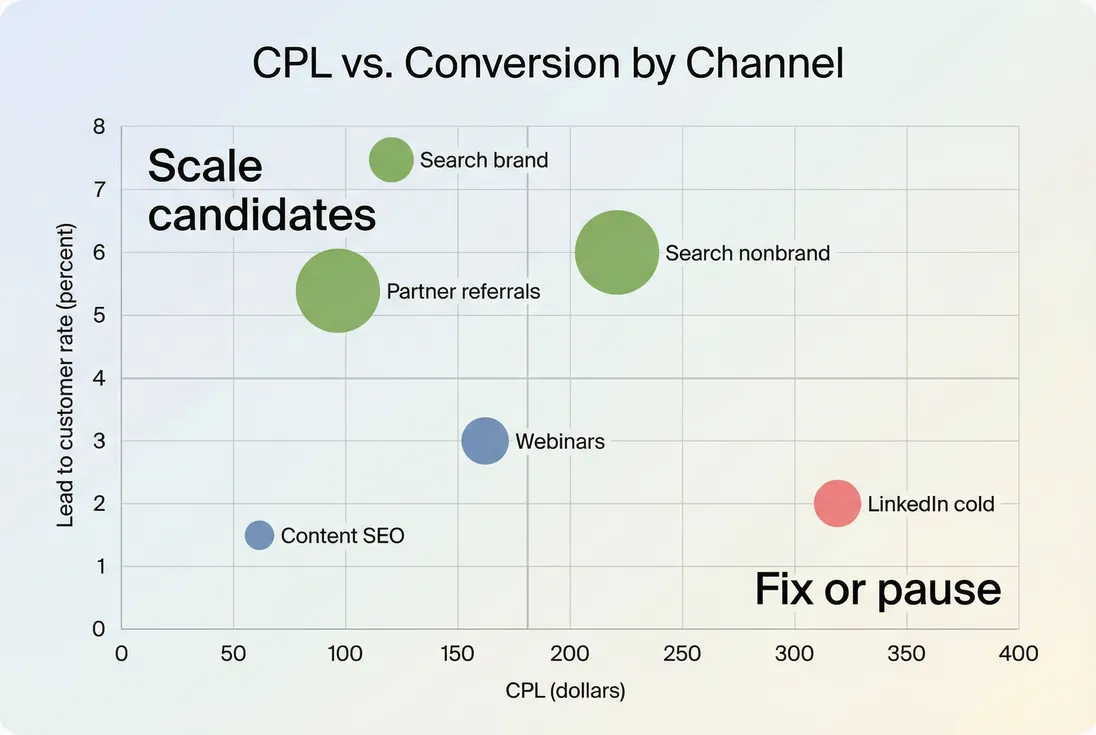

Channel comparisons that actually work

Because each channel has different conversion dynamics, founders should compare channels on two dimensions:

- CPL (efficiency)

- Lead-to-customer rate (quality)

Then add a third dimension when you can: expected customer value (ARPA/LTV).

Use CPL with conversion to separate "cheap but low intent" from "expensive but efficient" channels, then prioritize based on implied CAC and customer value.

What this chart enables in practice:

- Scale candidates: low-to-moderate CPL with strong conversion (often brand search, referrals, some high-intent search)

- Fix candidates: reasonable CPL but weak conversion (messaging, qualification, handoff speed)

- Pause candidates: high CPL and weak conversion (unless it produces higher-value customers, which you must prove)

Common CPL pitfalls (where teams fool themselves)

Blended CPL hides channel failures

A blended CPL can look stable while a core channel deteriorates and another improves. Always break out CPL by:

- Channel

- Campaign

- ICP segment (SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise)

- Offer type (demo vs content vs trial)

Lead spam and duplicates

As you reduce form friction, you may increase bot submissions and duplicates, which artificially lowers CPL. Basic hygiene:

- Deduplicate by email + company

- Filter obvious spam patterns

- Separate "valid leads" from raw submissions

Attribution window mismatch

If you count spend this week and leads next week, CPL gets noisy. Use consistent windows and, when possible, attribute leads by lead created date and costs by impression/click date within the same period.

Optimizing to the wrong stage

If your business is sales-led, CPL to raw leads is rarely the right optimization target. You'll usually get better decisions tracking CPL to SQL (or cost per opportunity) and pairing it with Qualified Pipeline.

The Founder's perspective

The cheapest leads are often the most expensive growth. If your SDR team complains about lead quality, don't argue with CPL—instrument the funnel so you can see where the "cheap" leads die.

Benchmarks: the only ones that matter

Generic CPL benchmarks are mostly noise because CPL depends on:

- ICP competitiveness

- Geo

- Channel mix

- Lead definition

- Offer type (demo vs content)

- Sales cycle length and ACV

Instead of chasing a universal benchmark, use internal benchmarks:

- Your trailing 8–12 weeks CPL by channel and lead type

- Your lead-to-customer rate by the same cuts

- Your implied CAC and payback targets

If you need a sanity check, treat any "benchmark" as a starting point, then validate with your own implied CAC math and retention outcomes (see Retention and Churn Rate).

A simple CPL operating cadence

For most early-to-growth SaaS teams, this cadence works:

- Weekly: review CPL, lead volume, landing page CVR, and lead-to-customer rate (early signal)

- Monthly: reallocate budget using implied CAC and pipeline/customer output (decision)

- Quarterly: revisit lead definitions and qualification rules (governance)

This keeps CPL in its proper place: an early warning system that informs spend—without letting it become the goal.

Frequently asked questions

A good CPL is the one that supports your target CAC and payback for a specific lead type and channel. For self-serve, you might tolerate higher CPL if the lead-to-paid rate is strong. For sales-led, judge CPL against cost per SQL and pipeline created, not raw leads.

Calculate CPL at the stage you can reliably standardize and act on. Raw leads are useful for creative and landing page optimization. MQL/SQL CPL is better for budget allocation because it bakes in lead quality. Many founders track all three to see where quality drops.

CPL is an upstream cost. CAC is the fully loaded cost to acquire a customer. If you know your lead-to-customer rate, you can translate CPL into implied CAC. This is where teams get fooled: a "better" CPL can still produce worse CAC if lead quality or sales conversion declines.

Include costs required to generate the lead: media spend, agency fees, contractor creative, and an allocation of marketing payroll tied to that program. Exclude sales costs unless you're intentionally measuring cost per SQL or cost per opportunity. Be consistent so trends reflect real performance changes.

Stop when low CPL fails to translate into downstream outcomes: SQLs, opportunities, customers, or revenue. A channel can look efficient at the lead stage while producing low-intent leads that waste SDR and AE capacity. Use a short test window, then decide based on implied CAC and payback.