Table of contents

COGS (cost of goods sold)

COGS is one of the fastest ways a SaaS company can "feel" like it's growing while actually getting less healthy. If every new dollar of MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) pulls a growing amount of infrastructure, vendor, or support cost behind it, you can scale revenue and still lose flexibility on hiring, pricing, and runway.

COGS (cost of goods sold) is the direct cost to deliver your product and keep customers successfully using it during the period you're measuring. In SaaS financials it's often labeled cost of revenue. It's the cost side of your gross margin.

Where COGS fits financially

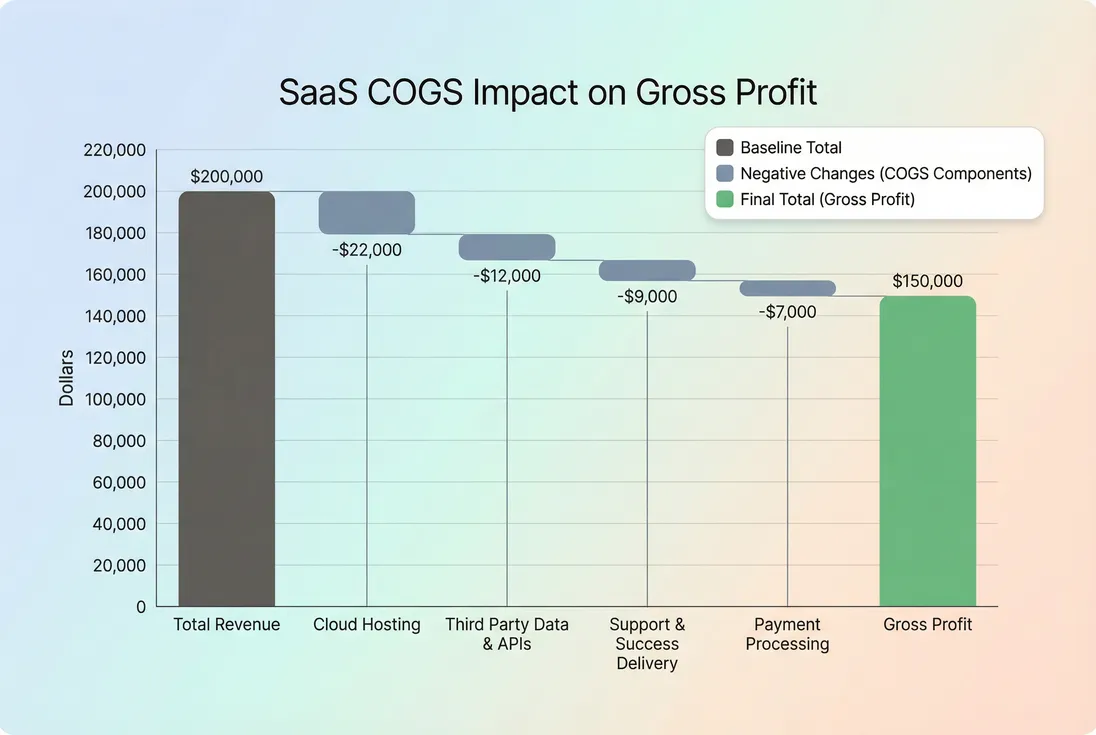

COGS sits between revenue and gross profit:

- Revenue (subscription, usage, etc.)

- Minus COGS (delivery costs)

- Equals gross profit

- Then operating expenses (R&D, sales, marketing, G&A)

- Then operating profit / cash flow

The reason founders care: COGS determines your gross margin, which is the "fuel" available to pay for growth (sales and marketing), product investment, and runway.

You'll also hear COGS percentage (or cost of revenue percentage):

A rising COGS rate is a structural problem unless you're deliberately shifting to a more service-heavy offering (and charging for it).

The Founder's perspective: I don't manage COGS to "look good" on a P&L. I manage it to keep pricing power and avoid scaling a model where each new customer quietly adds a support or infrastructure tax.

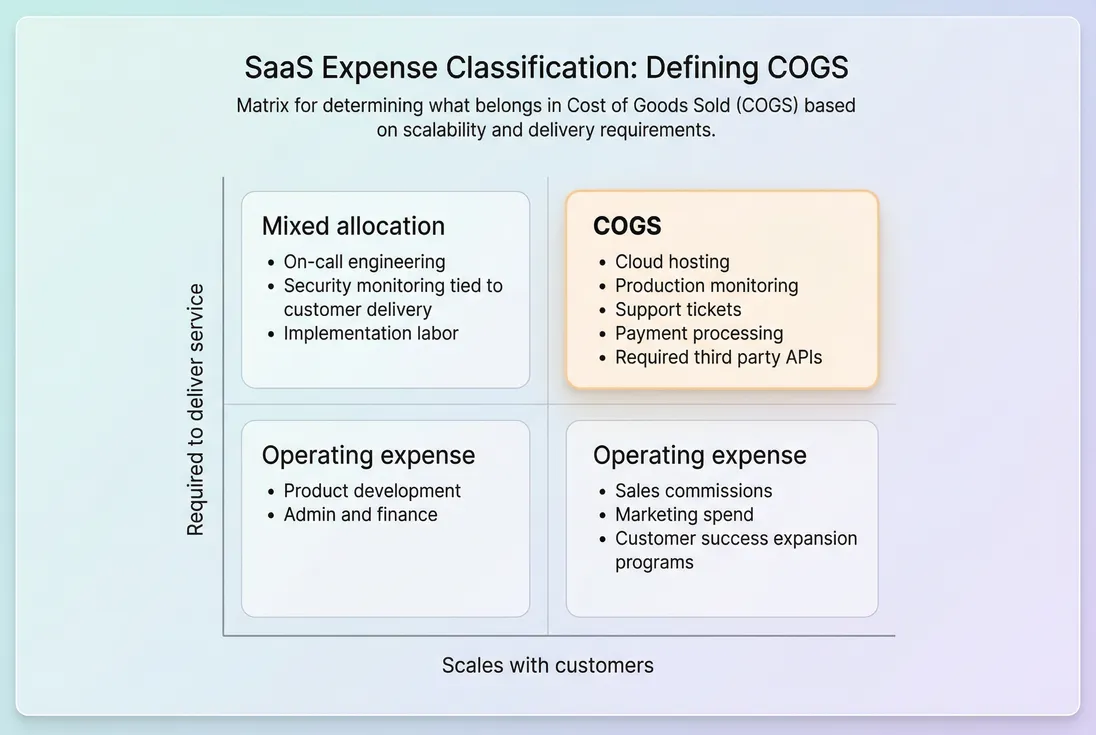

What counts as COGS in SaaS

The practical rule: If the cost is required to serve existing customers and scales with customers or usage, it's a COGS candidate.

Common SaaS COGS components

- Infrastructure and hosting

- Cloud compute, storage, bandwidth

- Observability tooling used to operate production (APM, logging) if directly tied to running the service

- CDN, queues, managed databases

- Third-party services required to deliver

- Data providers, enrichment APIs

- Email/SMS delivery used by the product

- AI inference or model hosting costs if your core product requires it

- Customer support and service delivery

- Support agents, on-call/SRE time spent keeping customers operational

- Implementation/onboarding labor if it's bundled and necessary to activate customers

- Payment processing and billing costs

- Stripe/processor fees, disputes, and some billing tooling

- See Billing Fees for how founders typically classify these

- Direct compliance delivery costs (sometimes)

- If a compliance service is effectively part of the delivered product (for example, required monitoring for a regulated workflow), some companies treat it as cost of revenue

What usually should NOT be in COGS

- Product development and engineering building new features (R&D)

- Sales and marketing expenses (including commissions)

- General and administrative costs (finance, HR, office)

- Most "growth CS" work (renewals, upsells) unless it's inseparable from baseline delivery

If you want a clean decision boundary: COGS is about keeping customers successfully served today. Operating expenses are about building and selling tomorrow.

The founder questions COGS answers

Founders rarely ask "what is COGS?" They ask questions like these.

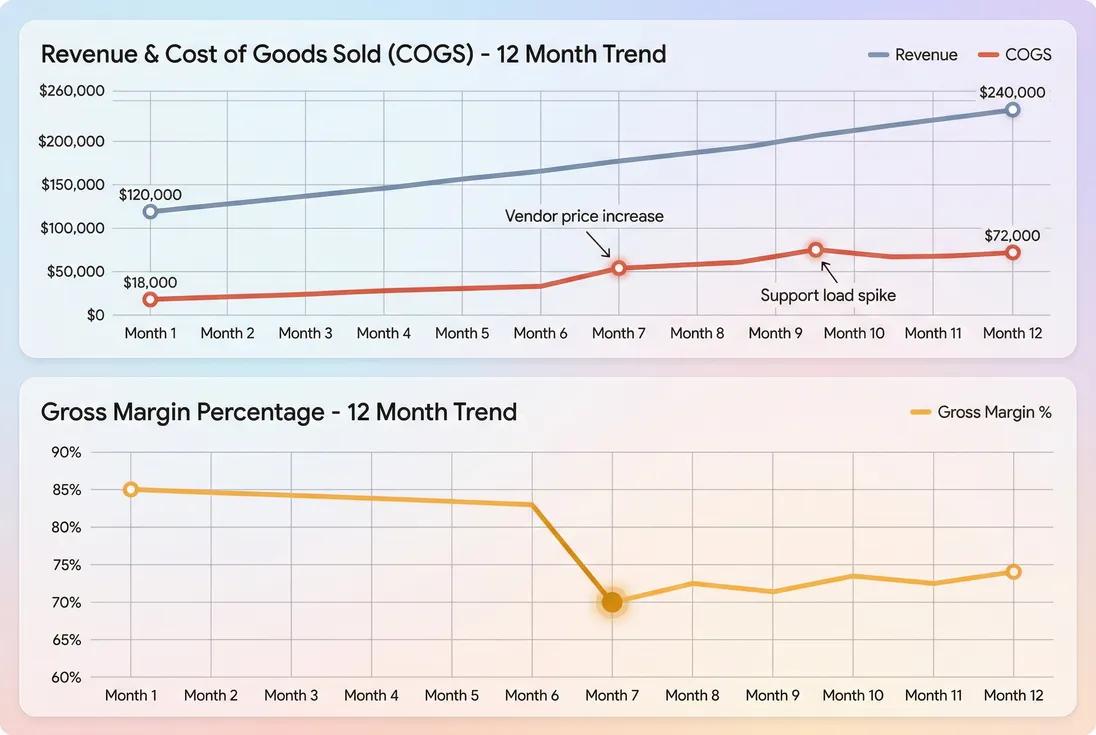

Are we scaling profitably?

COGS tells you whether growth creates gross profit or just creates more operational load.

A healthy pattern:

- Revenue grows

- COGS grows slower than revenue

- Gross margin stays stable or improves

A dangerous pattern:

- Revenue grows

- COGS grows at the same rate (or faster)

- Gross margin compresses

- Your Burn Rate rises because you need more people and tooling just to keep up

This is why COGS connects directly to capital efficiency metrics like Burn Multiple. If gross margin deteriorates, you have less gross profit to "buy" growth, which typically worsens your burn multiple even if top-line growth looks fine.

Quick benchmark ranges (rule of thumb)

| SaaS model | Typical gross margin | Typical COGS rate | What drives variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-serve B2B SaaS (pure software) | 80–90% | 10–20% | Efficient cloud, low support |

| Enterprise SaaS with onboarding | 75–88% | 12–25% | Implementation effort, support expectations |

| Usage-based / data-heavy SaaS | 60–85% | 15–40% | Compute, data, vendor pass-through |

| Services-heavy "SaaS + agency" | 40–70% | 30–60% | Human delivery embedded in revenue |

Benchmarks are only useful once you're honest about classification. If your support team sits in operating expenses, your "gross margin benchmark" is inflated and your comparisons are misleading.

Which customers are actually profitable?

Total COGS can look fine while specific segments are unprofitable. Founders should pressure-test COGS by segment:

- Plan tier (starter vs enterprise)

- Industry (compliance-heavy verticals)

- Integrations (data-heavy connectors)

- Contract type (usage-based vs flat fee)

A simple approach is to compute "fully loaded" COGS directionally by segment:

Even rough allocations can reveal the truth:

- Some large accounts generate high ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) but also demand heavy support.

- Some small accounts are low revenue but create disproportionate tickets (a classic "support sink").

The Founder's perspective: When we debate roadmap priorities, I want to know which features reduce COGS for our worst segments. A feature that cuts ticket volume or cloud usage can be worth more than a feature that adds a few points of conversion.

Are our prices and discounts sustainable?

COGS sets a pricing floor. If you price below your cost to serve (or discount aggressively), you may win deals that destroy gross profit.

A practical pricing sanity check:

Discounting compresses gross profit almost dollar-for-dollar because most COGS doesn't fall when price falls. If discounting is part of your go-to-market, tie it to:

- Longer contract length (Average Contract Length (ACL))

- Prepay

- Strict usage caps

- Reduced support entitlement

Also review Discounts in SaaS with a margin lens: the "real" cost of a discount is the gross profit you give away, not just the revenue.

What is driving COGS changes?

Founders should interpret COGS changes in two views: absolute dollars and unit economics.

COGS can rise for good reasons

- You added customers or usage increased (especially with Usage-Based Pricing)

- You improved reliability (more monitoring, better infra) and prevented churn

- You upgraded vendors to improve delivery

COGS rising is bad when unit costs rise

Watch for:

- Cloud cost per active customer rising

- Tickets per customer rising

- Vendor cost per delivered unit rising

- Payment processing fees rising faster than revenue (often due to pricing mix, chargebacks, refunds)

Refund activity can distort gross margin interpretation if your revenue reporting and COGS timing don't match; see Refunds in SaaS for the common operational causes and reporting implications.

A practical "COGS detective" checklist

When COGS surprises you, don't start with accounting. Start with operational drivers:

- Infrastructure

- Did cost per request or per active user increase?

- Did you ship a feature that multiplies compute?

- Any noisy neighbors, inefficient queries, or retention of large data?

- Support

- Ticket volume per customer: up or down?

- Are bugs causing repeat contacts?

- Are enterprise accounts requesting custom work?

- Vendors

- Did a provider change pricing tiers?

- Are you paying for unused capacity or overages?

- Billing

- Payment fees: did plan mix shift toward lower-priced plans (higher fee percent)?

- Are chargebacks increasing? (See Chargebacks in SaaS)

If you can't tie the change to one of these drivers, you likely lack cost allocation visibility—and you're flying blind on margin.

How to calculate COGS cleanly

The most common founder mistake is over-precision early and inconsistency later. Your goal is a COGS definition that is:

- Consistent over time

- Close enough to reality to drive decisions

- Auditable (you can explain it to an investor, acquirer, or finance hire)

Step 1: define your COGS policy

Write a simple one-pager:

- Which accounts and vendors are in COGS

- Which teams (or % of time) count as cost of revenue

- Where you draw the line between support delivery vs expansion work

This matters for M&A and diligence later; see M&A Readiness.

Step 2: match timing to revenue

Ideally, COGS aligns with the same period as recognized revenue (not cash collected). If you sell annual prepay, cash comes in upfront but service delivery cost happens monthly.

If you're still learning revenue recognition, review Recognized Revenue and Deferred Revenue. They explain why "cash in bank" and "revenue earned" diverge—and COGS should follow the earning pattern.

Step 3: track a small set of unit COGS metrics

Total COGS is necessary but not sufficient. Add 2–4 unit metrics that map to your model:

- COGS per active customer

- COGS per seat (if per-seat pricing)

- COGS per thousand events (if event-based usage)

- Support hours per account

- Infrastructure cost per workload unit

This is where pricing and packaging conversations become concrete.

How founders reduce COGS (without breaking the product)

Cost cutting in COGS is dangerous when it reduces reliability or support quality and increases churn. Tie every COGS optimization to a customer outcome metric (tickets, uptime, time-to-value).

Operationally, the best COGS reductions usually come from:

Infrastructure efficiency

- Remove waste (idle resources, over-provisioned databases)

- Make workload cost-visible (by feature, endpoint, or customer)

- Set budgets and alerts on key services

- Optimize data retention and query patterns

Technical debt is often a hidden COGS driver when it creates inefficient compute or unstable releases; see Technical Debt.

Product changes that lower support load

- Better onboarding flows and in-product guidance

- Fewer "gotchas" that create tickets

- Reduce time-to-value to lower hand-holding; see Time to Value (TTV)

Vendor strategy

- Renegotiate contracts as volume grows

- Replace expensive services with in-house alternatives only when scale justifies it

- Avoid "vendor sprawl" that creates duplicated capabilities

Align entitlements to margins

If enterprise accounts are margin-negative because support is unlimited, consider:

- Tiered support SLAs

- Paid implementation

- Usage caps or overage pricing

- Packaging that charges for high-cost features

The Founder's perspective: I don't want lower COGS if it increases churn. I want lower COGS per unit delivered while maintaining customer outcomes, so gross margin funds growth instead of patching operational leaks.

Common classification traps

Founders get tripped up by these edge cases:

- Customer success

- If they're doing renewals/upsells, it's not COGS.

- If they're effectively "keeping the lights on" for customers, some portion is COGS.

- Implementation and onboarding

- If bundled and required for the product to work, it behaves like COGS.

- If it's optional or paid separately, it's closer to services cost (and ideally priced for margin).

- R&D engineers on on-call

- On-call time supporting production can reasonably be allocated to cost of revenue, but be conservative and consistent.

- Security and compliance

- If it's general company compliance: operating expense.

- If it's a direct part of delivering the product to paying customers: sometimes cost of revenue.

- AI costs

- Inference can act like "cloud COGS" that scales with usage. If you price per seat but costs scale per message, margin can collapse fast.

How COGS connects to other metrics

COGS isn't a standalone KPI. It's a dependency for several metrics founders use to steer the business:

- Gross margin: see Gross Margin for deeper interpretation and targets.

- Contribution margin: if you subtract variable sales and marketing costs too, you get a clearer view of profit per dollar of growth; see Contribution Margin.

- LTV and payback: higher COGS lowers unit economics and lengthens payback; connect this with LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and CAC Payback Period.

- Net retention: if you push expansion that increases usage, make sure the incremental COGS doesn't erase the benefit; pair with NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and Net MRR Churn Rate.

A simple rule: Any strategy that increases usage should be evaluated on incremental gross profit, not just incremental revenue.

A founder-ready COGS cadence

If you want COGS to change decisions (not just appear in a board deck), run this monthly:

- Review gross margin trend (and explain every meaningful change)

- Break COGS into 4–6 components (cloud, vendors, support, payment fees, delivery labor)

- Track 2–4 unit COGS metrics (per customer, per seat, per usage unit)

- Identify one COGS driver to fix (a cloud spike, a vendor tier, a support driver)

- Tie the fix to customer outcomes (fewer tickets, better uptime, faster onboarding)

That cadence keeps COGS from becoming "finance trivia" and turns it into a real operating lever—one that protects gross margin, improves capital efficiency, and makes your growth more durable.

Frequently asked questions

Include costs that scale with delivering and supporting the product: cloud hosting, third party infrastructure, payment processing, customer support, and service delivery labor tied to live accounts. Exclude product development, sales and marketing, and general admin. Be consistent quarter to quarter so gross margin trends are meaningful.

Most pure software SaaS targets 10 to 25 percent COGS, or 75 to 90 percent gross margin. Usage based, data heavy, or AI inference products may land at 20 to 40 percent COGS. If you are under 70 percent gross margin, investigate infrastructure efficiency and support load before scaling spend.

It depends on what the team does. Reactive support needed to keep the service running and customers unblocked is usually COGS. Proactive expansion work, renewals, and adoption programs are typically operating expense. If roles are blended, allocate time or headcount percentages so your gross margin is not artificially inflated.

Discounts reduce revenue but do not reduce most COGS, so they directly compress gross margin. A 20 percent discount often drops gross margin by more than 20 percent if COGS is meaningful. Use a COGS informed pricing floor and review [Discounts in SaaS] decisions with margin impact, not just win rate.

Common causes are vendor price increases, higher cloud usage per customer, a support surge from outages or product issues, or adding compliance and data tooling that is treated as cost of revenue. Break COGS into components and look for per account or per usage step changes before assuming churn or pricing is the culprit.