Table of contents

Capitalized development costs

If you don't understand your capitalized development costs, you can "improve" EBITDA while your cash burn stays exactly as bad. That's how founders get blindsided in board meetings, fundraising diligence, and M&A. The payoff of tracking this correctly is simple: cleaner burn conversations, fewer valuation surprises, and better decisions on hiring, roadmap, and runway.

Capitalized development costs are software/product development costs that you record as an asset on the balance sheet (instead of expensing immediately on the P&L) because they are expected to generate future economic benefit. Those costs then hit the P&L later through amortization.

Why founders track capitalization

You care because capitalization changes the story your financials tell—especially when you're trying to answer questions like:

- Are we efficiently turning engineering dollars into durable product?

- Is our Burn Rate actually improving, or just our accounting?

- Will our Burn Multiple survive investor normalization?

- Are we investing in long-lived platform work or endless "one-off" customer work?

Here's the core dynamic:

- Expensing puts the cost on the P&L now. It makes current losses larger, but it's straightforward.

- Capitalizing moves qualifying costs to the balance sheet now and spreads the expense over time via amortization. It makes current losses smaller, but increases future amortization.

The founder's perspective

Capitalization is not a growth lever. It's a reporting choice bounded by accounting rules. If you need capitalization to "hit the plan," your plan is lying to you.

Capitalization also affects behavior. If you set aggressive capitalization targets, teams will (consciously or not) relabel work as "new platform development" instead of "maintenance," because it makes the numbers look better. That is a governance problem, not an accounting detail.

What gets capitalized (and what doesn't)

The biggest mistake founders make is thinking "development costs" means "engineers." It doesn't. It means specific work, in specific phases, that meets specific criteria.

This varies by accounting framework (US GAAP vs IFRS) and your company's policies. Talk to your accountant. But operationally, the rules usually boil down to this:

Costs that are often eligible

- Direct labor: engineering time spent building a defined feature/product that will be used over multiple periods.

- Directly attributable costs: contractor development work, certain software tools directly tied to development (policy-dependent), and sometimes payroll taxes/benefits allocations.

- Development phase work: after feasibility is established and you're building something you expect to deploy and benefit from.

Costs that are usually not eligible

- Research / exploration: "we're figuring out what to build" time.

- Maintenance: bug fixes, small tweaks, routine upgrades, refactoring that doesn't add new capability (often treated as upkeep).

- Customer-specific one-offs: especially if the benefit is tied to a single contract and not reusable.

- Training, support, sales enablement: not development.

- Post-launch operational work: running the system, incident response, on-call.

A practical way to think about it: if you couldn't convincingly argue the work creates a reusable asset with multi-period benefit, don't capitalize it.

The founder's perspective

If your roadmap changes every two weeks, your "future benefit" case is weak. Capitalization will look aggressive, even if you technically can justify pieces of it.

How to calculate it (without getting lost)

Founders don't need a CPA-level model. You need three numbers that reconcile cleanly:

- Additions (what you capitalized this period)

- Amortization (what you expensed from prior capitalized work)

- Ending asset balance (what sits on the balance sheet)

Two formulas keep you grounded.

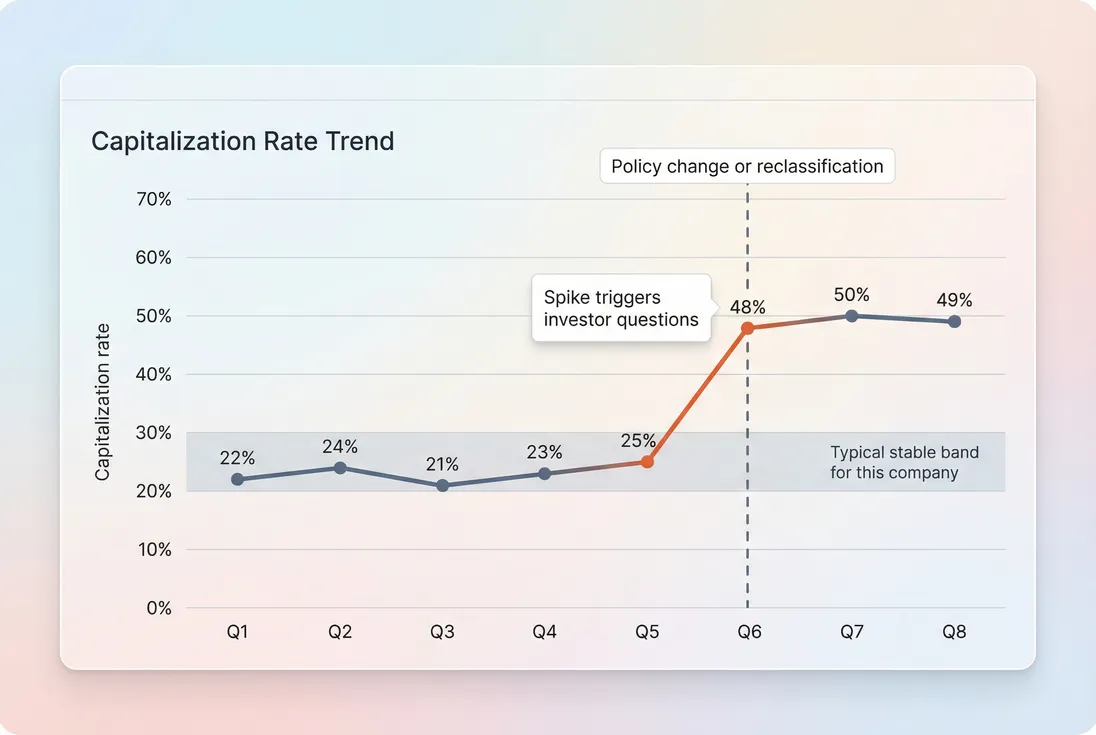

1) Capitalization rate (your operating reality check)

Interpretation:

- Higher rate means more of engineering spend is treated as creating a long-lived asset.

- Lower rate means more is treated as period expense (or you're earlier stage / more exploratory).

This is where founders get sloppy: they compare capitalization dollars across months when headcount is changing. Track the rate, not just the absolute number.

2) Reported development expense (why your P&L can mislead)

Interpretation:

- If you capitalize more this month, reported expense drops (even though cash doesn't).

- If your amortization builds up, reported expense rises later (even if you slow hiring).

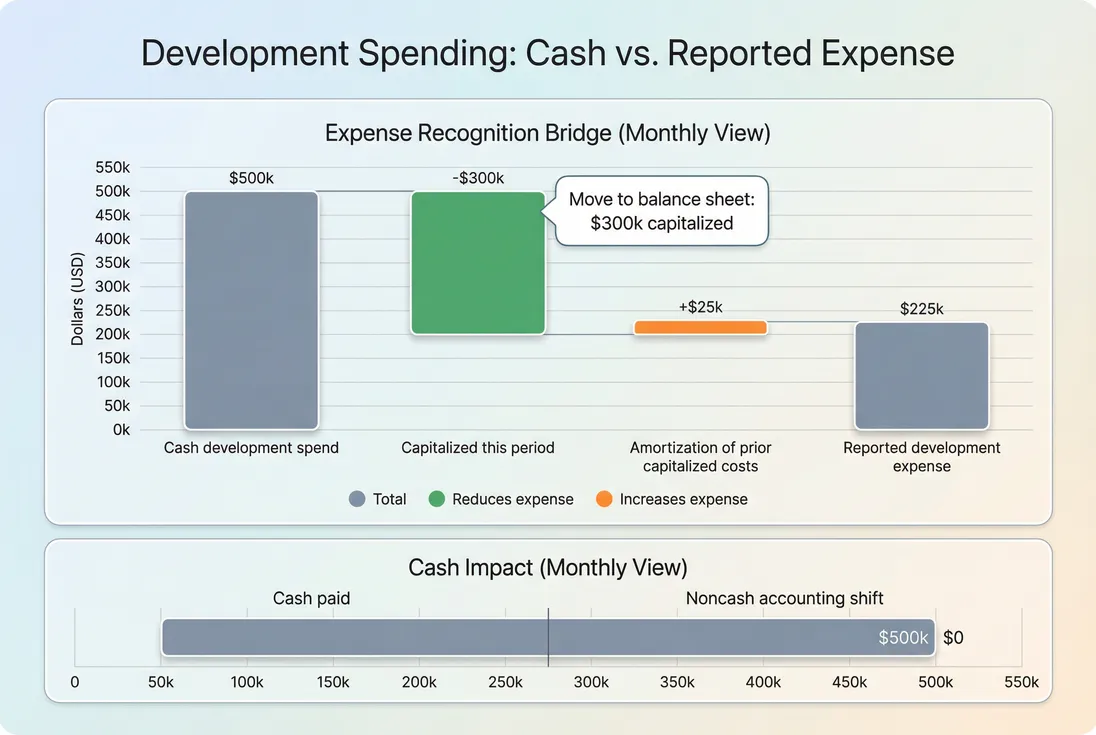

A concrete example (numbers you'll actually see)

Assume in one month you spend:

- $500k on development payroll and contractors (cash impact)

- You capitalize $300k (eligible work, properly tracked)

- You amortize $25k from prior capitalized projects (noncash expense)

Then:

- Reported development expense = $500k − $300k + $25k = $225k

- Cash burn still reflects $500k leaving the bank (ignoring timing differences)

This gap is the whole point: capitalization changes timing of expense recognition, not the reality of spending.

How to interpret it in practice

You're not trying to "maximize capitalization." You're trying to keep three things true:

- Your capitalization policy reflects how you actually build product.

- Your financials are comparable over time.

- You can defend it under diligence.

The three numbers to watch every month

- Capitalization rate (trend + volatility)

- Amortization as a percent of revenue (drag on future margins)

- Capitalized development asset balance (and how fast it's growing)

Here's how to read the trend like an operator.

If capitalization rate is rising

This can be good if:

- You've shifted from experimentation to scalable platform work

- You now have repeatable delivery processes (better specs, less thrash)

- You're building durable infrastructure that will support future ARR

It's bad if:

- It spikes right before fundraising

- It rises because you reclassified maintenance as "new development"

- It's masking an R&D org that's not shipping usable value

If amortization is rising

This is the "bill comes due" effect. It means prior capitalization is now flowing through the P&L.

What you do:

- Forecast amortization explicitly in your operating plan.

- Don't celebrate an "expense reduction" that is just temporary capitalization timing.

- If amortization is growing faster than revenue, you're building an asset stack that will compress future margins.

This ties directly into profitability metrics like Operating Margin and cash metrics like Free Cash Flow (FCF). The P&L may look smoother, but cash planning must remain brutally literal.

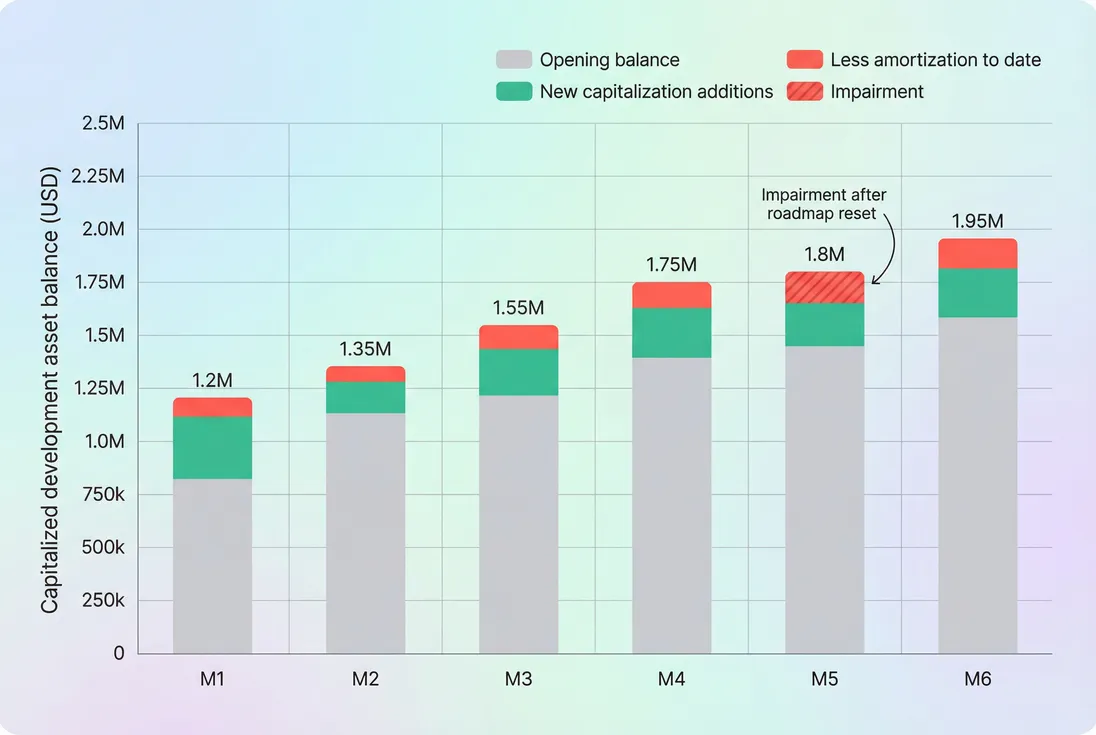

If the asset balance is growing fast

Growing capitalized development assets can be fine—if the product is compounding. It's a problem when it's not.

A simple diagnostic question: Is the product getting meaningfully better for customers in a way that drives retention or expansion? If not, you may be capitalizing "work" rather than "value."

If you want to connect it to revenue reality, tie major capitalization projects to:

- retention improvements via Cohort Analysis

- expansion impact via NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and Expansion MRR

- pricing power via ASP (Average Selling Price) or ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)

Not because accounting should follow dashboards—but because the business case for capitalization is future benefit. If there's no benefit, the asset is questionable.

Benchmarks and tradeoffs (what "good" looks like)

There isn't a universal "good capitalization rate." But there are clear tradeoffs and patterns that show maturity vs manipulation.

| Pattern | What it might mean | Upside | Risk / downside | What you should do |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low and stable capitalization | Early-stage, exploratory work, or conservative policy | Clean comparability, low scrutiny | P&L looks worse; may understate "asset-building" | Manage runway on cash; explain product investments qualitatively |

| Moderate and stable capitalization | Mature dev process, clear project scoping | Better matching of cost to benefit | Requires discipline and tracking overhead | Keep policy consistent; forecast amortization |

| Rising capitalization rate with stable delivery | Shift to platform, reusable components | P&L improves while investing | Easy to over-capitalize maintenance | Audit eligibility quarterly; tie projects to product outcomes |

| Sudden spike | Reclassification or fundraising cosmetics | Short-term optics | Investor normalization, credibility hit | Preempt with documentation and rationale; don't hide it |

| Large asset + frequent impairments | Roadmap churn, failed bets | None | You're capitalizing work you don't keep | Tighten product strategy; stop capitalizing borderline work |

The founder's perspective

Investors don't punish you for expensing. They punish you for surprises. A conservative policy with clean cash reporting beats an aggressive policy that gets "normalized" anyway.

When this metric breaks down

Capitalized development costs are most useful when your business is building durable product. They break down when your environment is chaotic.

Red flags that trigger diligence pain

- No time tracking or weak allocation logic

If you can't tie capitalized labor to specific projects/phases, expect pushback. - Useful life assumptions that feel convenient

Longer amortization periods reduce near-term expense. They also look suspicious if your product changes fast. - Capitalizing customer-driven one-offs

If a "feature" only exists because one customer demanded it, the future benefit case is weak. - Capitalization used to "hit EBITDA"

Boards and investors can smell this. They'll adjust your numbers and discount your narrative.

The real operational risk: you stop seeing R&D inefficiency

Aggressive capitalization can make it harder to notice:

- bloated teams

- low shipment velocity

- roadmap thrash

- overbuilding

Your cash burn tells the truth. Your capitalized costs can hide it.

So if you track one "counter-metric," make it this: cash engineering spend as a percent of revenue, independent of accounting treatment. Pair it with Revenue per Employee to keep hiring honest.

How founders use it

Here's the operator-grade playbook.

1) Run two views of performance

- Cash view (decision view): headcount, vendor spend, runway

- Accounting view (reporting view): capitalization, amortization, operating profit

If you force yourself to make hiring and roadmap decisions on the cash view, capitalization becomes what it should be: a reporting method, not a steering wheel.

2) Set a policy you can defend, then stick to it

Consistency beats cleverness.

- Define what "eligible" means in your context (examples, exclusions).

- Define phases (research vs build vs post-release).

- Define documentation expectations (tickets, project codes, time allocation rules).

Then don't change it casually. If you do change it, document the reason like you're writing to a skeptical acquirer.

3) Treat capitalization like a product ops metric

Not because it's "product performance," but because it reflects development maturity.

- Stable capitalization rate often correlates with clearer specs and less thrash.

- Erratic capitalization often correlates with chaos (and future impairments).

Use it as a forcing function: if you can't clearly separate "build" from "maintenance," your planning discipline is probably weak.

4) Forecast amortization like it's real expense (because it is)

Your future P&L will carry amortization even if you slow hiring. That matters for:

- margin targets

- covenant conversations (if you have debt)

- valuation narratives

A simple planning rule: every time you approve a big capitalization project, ask, "What amortization does this create next year?"

5) Don't let it distort customer economics narratives

If you're discussing efficiency with investors, they'll triangulate with:

- Burn Multiple

- growth rate

- retention and churn metrics (like NRR (Net Revenue Retention))

- and sometimes a normalized EBITDA that expenses development

So be explicit:

- "Here is our reported operating loss."

- "Here is our cash burn."

- "Here is our capitalization policy and rate over time."

- "Here is what changes if you expense it."

That transparency prevents the "gotcha" moment later.

What to do next

If you want this to actually improve decision-making (not just reporting), do these in order:

- Pull the last 12 months of development cash spend, capitalized additions, and amortization. Build a simple rollforward.

- Calculate capitalization rate monthly and look for spikes or trend breaks.

- Write a one-page capitalization policy with examples of eligible vs ineligible work.

- Tie capitalized projects to business outcomes (retention, expansion, pricing power). If you can't, question the "asset" premise.

- Plan runway using cash, not P&L. Use Burn Rate and Runway discipline regardless of capitalization.

Capitalized development costs are fine. Abusing them is expensive. The goal is credibility and control: you know what's happening, you can explain it in one minute, and you're not making operational decisions based on accounting optics.

Frequently asked questions

It can be, if you use it to make EBITDA prettier without changing product output. But it's also legitimate matching of costs to future benefit. Founders should treat it as an accounting policy with real constraints, then manage to cash, not reported profit.

There's no universal benchmark because rules differ by GAAP vs IFRS and by what you build. Early-stage teams often capitalize little because work is exploratory. Later-stage teams with repeatable delivery may capitalize more. Track consistency and rationale; sudden spikes are what investors distrust.

No. It doesn't change cash. It can improve reported operating loss by shifting expense to the balance sheet, but payroll still leaves your bank account. If you manage runway using P&L after capitalization, you'll overestimate how long you can survive.

Many normalize it by expensing a portion (or all) of capitalized costs to compare companies consistently. They look for stable policy, clean time tracking, and reasonable useful lives. If your capitalization is aggressive, expect a haircut to EBITDA and valuation multiples.

If you can't defend eligibility, don't have reliable time tracking, or your roadmap shifts constantly, expensing is safer. Also consider expensing if capitalization distracts the team, creates internal incentives to label work incorrectly, or masks real efficiency issues in R&D.