Table of contents

CAC payback period

If you don't know your CAC payback period, you're guessing how much growth your business can "self-fund." That guess shows up later as surprise cash crunches, hiring freezes, and marketing whiplash.

CAC payback period is the number of months it takes to earn back your customer acquisition cost (CAC) using the gross profit generated by a new customer. In plain English: how long your money is tied up before a new customer becomes net-positive.

This metric matters because it connects go-to-market decisions (spend, headcount, pricing) directly to cash risk and capital efficiency.

What payback reveals

CAC payback period answers one operational question: how quickly acquisition spend returns to you so you can reinvest it.

Founders use it to make decisions like:

- Can we afford to scale paid acquisition, or do we need to slow down?

- Should we hire more sales reps now, or wait until unit economics tighten?

- Are discounts or longer contracts actually improving economics, or just optics?

- Which segment/channel can safely absorb higher CAC?

Payback also prevents a classic mistake: celebrating top-line growth while your acquisition engine is quietly consuming cash faster than you can replenish it.

The Founder's perspective: If payback is drifting longer, treat it like a leading indicator of future constraint. It usually shows up in the bank account months later—after you've already committed to spend and headcount.

How to calculate payback

There are two common ways to calculate CAC payback. One is a quick "steady-state" estimate (great for weekly/monthly management). The other is cohort-based (best for accuracy and for diagnosing issues).

The steady-state formula (most common)

At its simplest, payback is CAC divided by monthly gross profit from the average new customer.

Where:

- CAC is your CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) for the segment/channel you're measuring.

- ARPA per month is ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) (monthly).

- Gross margin is from Gross Margin (expressed as a decimal like 0.80).

Example

- CAC = 6,000

- ARPA = 500 per month

- Gross margin = 0.80

Monthly gross profit = 500 × 0.80 = 400

Payback = 6,000 / 400 = 15 months

This is the version you can put on a dashboard and use as a guardrail.

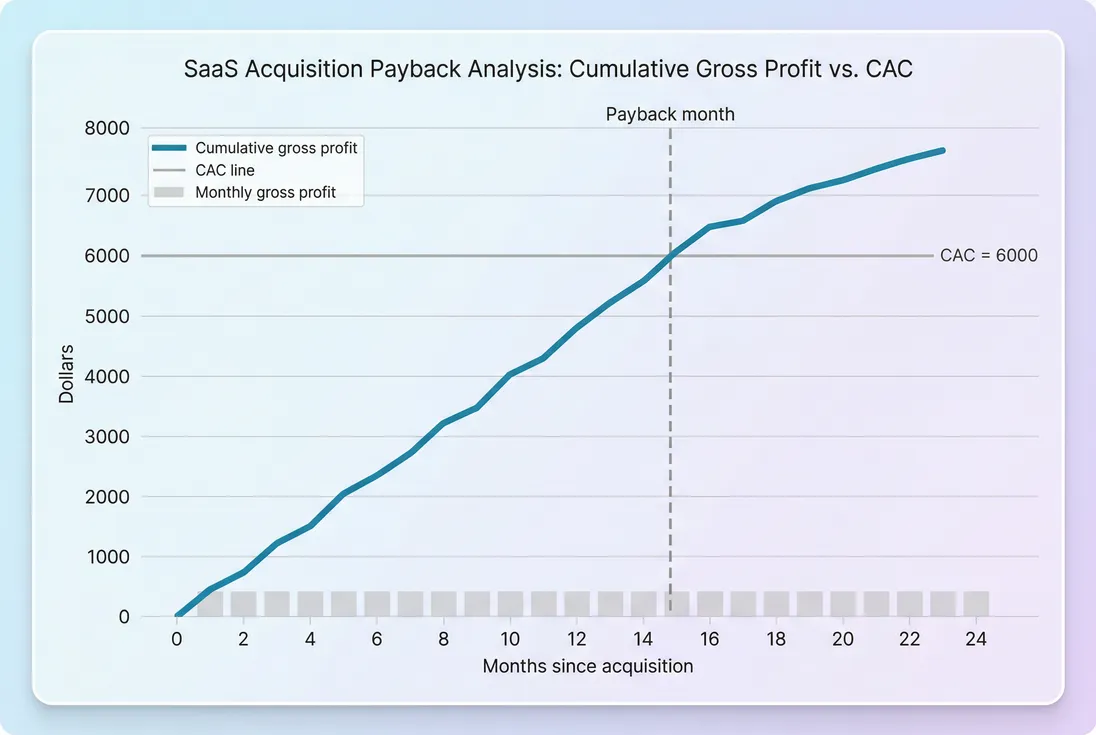

Cohort-based payback (more accurate)

Real customers don't behave like "average steady-state" customers:

- revenue ramps after onboarding

- expansions happen later

- churn happens early for poor-fit cohorts

- variable costs can change with usage

Cohort payback asks: in which month does cumulative gross profit from a cohort first exceed CAC?

Use cohort payback when:

- you've changed pricing/packaging

- you're shifting channels (e.g., outbound to paid)

- you sell annual plans or have heavy onboarding ramps

- retention differs significantly by segment

A good companion is Cohort Analysis, because payback is ultimately a cohort story: how the customers you acquired in a given period behave over time.

What exactly belongs in CAC?

Payback is only useful if CAC is defined consistently. A practical approach:

- Include: sales and marketing payroll, commissions, contractor spend, paid media, tools, content costs, events—anything required to acquire customers.

- Decide deliberately: do you include SDR/AE ramp time, marketing leadership, brand spend?

- Be consistent: changing inclusions makes the trend meaningless.

If you need a sanity check, start with the definition in CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) and document your inclusions like an accounting policy.

The Founder's perspective: If your team debates CAC inclusions every month, you don't have a payback metric—you have a negotiation. Pick a definition that matches how you actually run the business, then lock it for at least two quarters.

What drives payback up or down

Payback moves for only three fundamental reasons:

- CAC changes (numerator)

- Unit gross profit changes (denominator)

- Timing changes (when gross profit arrives)

Here are the main levers, how they show up, and what to do about them.

1) CAC goes up (payback gets longer)

Common causes:

- channel saturation (higher CPCs, lower conversion)

- sales cycle expansion (more touches, more labor)

- lower win rates due to weaker ICP fit (see Win Rate)

- higher competition pushing discounting (see Discounts in SaaS)

What to do:

- split payback by channel and segment (blended numbers hide problems)

- tighten qualification (quality beats volume when payback is fragile)

- improve lead-to-customer mechanics (see Lead-to-Customer Rate)

2) ARPA rises (payback gets shorter)

ARPA can rise through:

- price increases

- packaging that captures more value

- moving upmarket (see ASP (Average Selling Price))

- expansions (see Expansion MRR)

Important nuance: ARPA can rise while retention worsens. If higher prices increase early churn, payback might look fine in steady-state math but fail in cohort payback.

3) Gross margin improves (payback gets shorter)

Gross margin is often underestimated as a growth lever. Improving margin shortens payback without changing CAC or pricing.

Typical drivers:

- infrastructure optimization

- reducing support burden through better onboarding

- improving payment performance and reducing leakage (see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS)

If your service delivery costs vary by segment, consider using Contribution Margin to get a more decision-useful payback.

4) Timing shifts (payback "breaks")

Two companies can have identical CAC, ARPA, and gross margin—but different payback—because gross profit arrives at different times.

Common timing issues:

- Revenue ramp: customers start small and expand later (good long-term, painful short-term)

- Implementation/onboarding delay: you can't bill until go-live

- Annual prepay: cash arrives now, revenue is recognized over time

- Collections delays: invoices paid late (see Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging)

This is why teams often track both:

- Economic payback (gross profit based; best for unit economics)

- Cash payback (collections based; best for runway planning)

What good looks like

"Good" depends on your business model and your risk tolerance (cash, churn, and sales motion). Still, founders need operating ranges to set budgets and hiring plans.

Practical benchmarks (by motion)

| Motion / context | Typical payback target | Why |

|---|---|---|

| PLG SMB (low-touch) | 3–9 months | Lower CAC, faster activation, faster signal on retention |

| SMB / mid-market sales-led | 6–12 months | Moderate CAC; need room for rep ramp and variability |

| Enterprise sales-led | 12–18 months (sometimes 24) | High CAC and long sales cycles, often offset by strong retention and expansions |

| Usage-based with ramp | Use cohort payback | Early revenue understates true economics |

Two grounding rules:

- If payback is longer than your realistic cash horizon, growth will force a financing event. Pair it with Runway and Burn Rate.

- If payback is "great" but churn is high, it's fragile. Check Logo Churn and NRR (Net Revenue Retention).

The Founder's perspective: Payback is a constraint, not a trophy. Your "best" payback number is one that supports your growth plan without forcing desperate fundraising or underinvesting in product and retention.

Set a target, then back into CAC

Once you choose a payback target (say, 12 months), you can translate it into a maximum CAC your business can tolerate at current ARPA and margin.

Example:

- Target payback = 12 months

- ARPA = 500

- Gross margin = 0.80

Max CAC = 12 × 500 × 0.80 = 4,800

This turns payback into an acquisition budget guardrail your team can actually enforce.

How founders use payback in decisions

Payback becomes powerful when it changes what you do next week—not just what you report next month.

1) Decide whether to scale spend

If payback is within target and stable, you can scale spend with more confidence. If it's drifting longer, scaling often compounds the problem because you're increasing the amount of cash tied up.

Pair payback with:

- Burn Multiple for overall efficiency

- Capital Efficiency for board/investor narratives

- SaaS Magic Number for sales and marketing efficiency trends

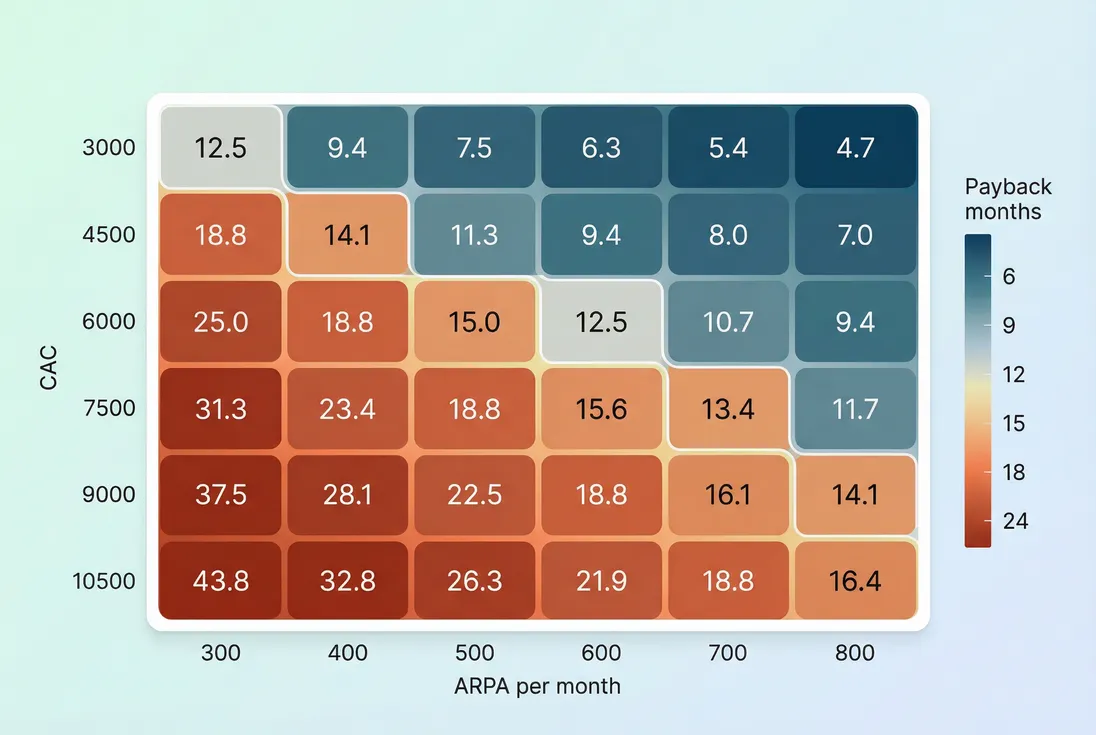

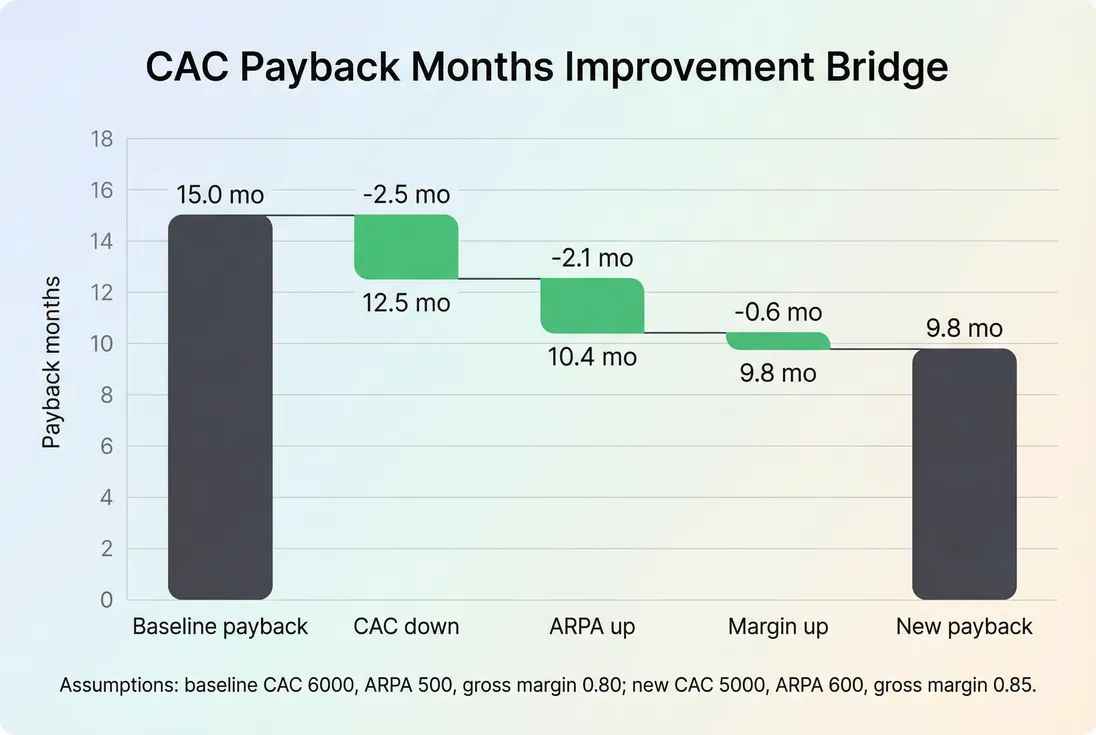

2) Choose where to invest: CAC vs ARPA vs margin

A useful way to think about payback optimization is: which lever is cheapest to move?

- If paid CAC is rising, it might be cheaper to improve conversion or tighten ICP than to "outspend" the market.

- If ARPA is low, pricing and packaging work can shorten payback without adding headcount.

- If gross margin is weak, infrastructure and support cost improvements may be your fastest win.

3) Govern discounting and contract terms

Discounts can "buy" shorter payback only if they increase close rates enough to offset lower ARPA—or if they meaningfully reduce CAC (less sales time, faster cycles). Otherwise, discounting usually lengthens payback.

When discounting becomes common, look at:

- Discounts in SaaS (mechanics and pitfalls)

- Average Contract Length (ACL) (longer commitments may improve cash timing)

- Sales Cycle Length (shorter cycles often reduce CAC)

4) Diagnose go-to-market changes faster

Payback is slow to fully "realize" (you need months of data), but it can still be used as an early-warning system when you:

- track it by segment/channel

- use a trailing average like T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average)

- pair it with leading indicators (win rate, early churn, activation)

Common traps that mislead founders

Using revenue instead of gross profit

Payback based on revenue ignores your delivery costs. If margin is changing (usage, support load, infra), revenue-based payback can give false confidence.

Relying on blended CAC

Blended CAC hides channel mix shifts. If your low-cost channel slows and you replace it with a higher-cost one, blended CAC can look stable while the underlying engine degrades.

Ignoring early churn

Averages assume customers stick around long enough to pay back. If early churn spikes, cohort payback can go from "12 months" to "never."

Use churn metrics alongside payback:

Confusing cash payback with economic payback

Annual prepay can make cash payback look fantastic even if economic payback is mediocre. If you're making scaling decisions, don't let cash timing hide weak unit economics.

Treating payback as a single KPI

Payback is strongest when it's segmented:

- by channel (paid search vs outbound vs partner)

- by customer size (SMB vs mid-market)

- by plan or pricing model (see Usage-Based Pricing)

The Founder's perspective: A single blended payback number is usually "politically useful" and operationally useless. Segment it until it tells you what to do—then stop.

A simple operating checklist

If you want CAC payback to drive real decisions, implement this cadence:

- Define CAC once (inclusions, time window, attribution rules).

- Track payback by segment and channel (not just blended).

- Use steady-state payback weekly/monthly as a guardrail.

- Validate with cohort payback quarterly to catch timing and churn effects.

- Tie targets to runway using Burn Rate and Runway.

- Cross-check with LTV using LTV:CAC Ratio so you don't optimize for fast payback at the expense of long-term value.

When CAC payback is tight and stable, you earn the right to scale. When it stretches, you either fix the unit economics—or you accept that growth will require more capital and more risk.

Frequently asked questions

Most SaaS teams target 6–12 months for SMB and mid-market, and 12–18 months for enterprise motions with strong retention. Earlier-stage companies can tolerate longer payback if cash is ample, growth is efficient elsewhere, and churn is low. Use segment benchmarks, not one blended number.

Use gross margin for a clean, comparable standard. Use contribution margin when onboarding, support, implementation, or usage costs are materially different by segment and you want a truer cash-like view of scaling that segment. The key is consistency: pick one definition, document inclusions, and keep it stable over time.

Annual prepay can dramatically improve cash payback because you get cash up front, but it does not necessarily improve economic payback if you still recognize revenue over time and margins are unchanged. Track both: an economic payback based on gross profit, and a cash payback based on collections.

Payback can improve if ARPA rises or gross margin improves, but burn can still worsen if you scale headcount, ramp sales reps, increase R&D, or spend ahead of demand. Payback is a unit economics metric; burn reflects total cost structure. Pair payback with Burn Rate and Burn Multiple.

Set a company-level guardrail based on runway, then allocate tighter targets to riskier or lower-retention channels. For example, paid social might need faster payback than partner referrals if quality is noisier. Enforce targets with channel-level CAC, early retention, and cohort-based payback, not blended averages.