Table of contents

CAC (customer acquisition cost)

Founders rarely run out of ideas—they run out of efficient acquisition. CAC is the metric that tells you whether growth is getting easier, staying stable, or becoming painfully expensive. If CAC drifts up without you noticing, you can wake up six months later with "growth" that quietly destroyed your cash position.

Customer acquisition cost (CAC) is the total cost to acquire new paying customers in a period, divided by the number of new paying customers acquired in that period. In plain terms: how much you spent to get one new customer.

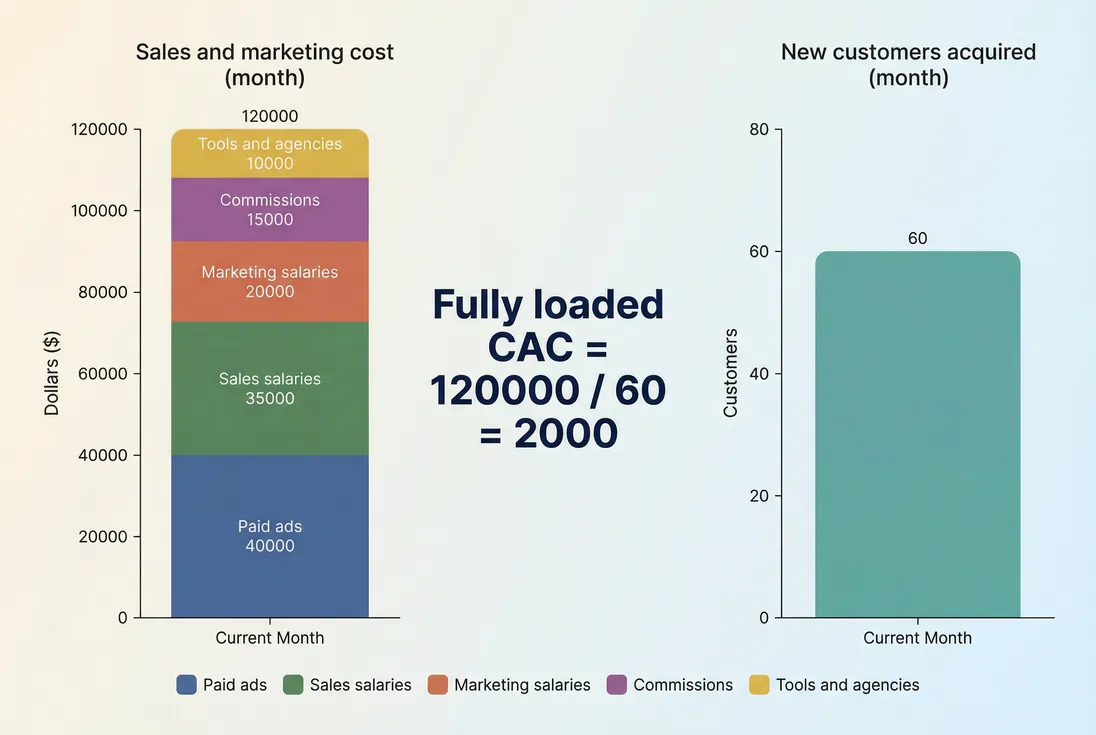

What CAC actually includes

CAC sounds simple, but teams get misaligned because they use different "cost buckets." Decide which version you're using, and use it consistently.

The two CAC definitions worth tracking

- Paid (or variable) CAC

Useful for channel optimization and experiments.

- Ad spend

- Sponsorships

- Affiliate commissions

- Freelancers/agencies tied to acquisition

- Fully loaded CAC

Useful for budgeting, hiring, and runway planning.

- All paid CAC items, plus:

- Sales team payroll

- Marketing team payroll

- Sales commissions and spiffs

- Sales development (SDR/BDR) costs

- Tools: CRM, sequencing, intent, data providers

- Events (if acquisition-driven)

What to typically exclude from CAC (but document your policy):

- Core R&D/product payroll

- Finance/legal

- Broad G&A rent and admin (unless your model requires it to acquire customers)

The Founder's perspective: If you're deciding whether to hire two AEs or double paid spend, you need fully loaded CAC. If you're deciding whether to scale LinkedIn ads or cut them, you need paid CAC. Confusing the two produces confident decisions with bad inputs.

How to calculate CAC correctly

The core formula is straightforward:

The "gotchas" are almost always about timing and counting.

Step 1: Define the denominator precisely

Most SaaS teams should use:

- New paying customers (new logos) created in the period

Not trials started, not leads, not opportunities.

Be explicit about edge cases:

- Free to paid conversions: count them as new customers, but make sure the costs that created them are included.

- Reactivations: generally exclude from "new customers" and track separately (they're not new acquisition).

- Expansion-only closes: not new customers; they affect retention metrics like NRR (Net Revenue Retention), not CAC.

If you're sales-led, your denominator is often "new customers closed-won." If you're product-led, it might be "new self-serve paying subscribers."

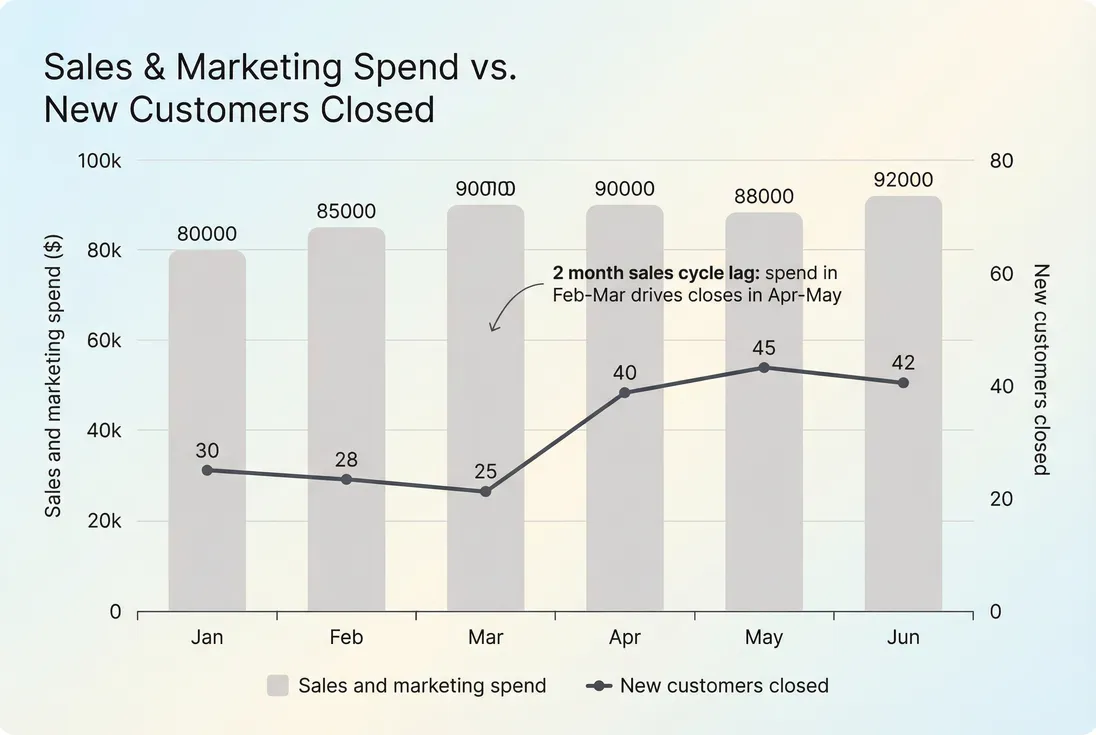

Step 2: Decide the time window (and handle lag)

A common mistake is calculating CAC monthly when your sales cycle is 45–120 days. That makes CAC look volatile and misleading because costs happen before closes.

Two practical approaches:

- Lagged CAC: attribute costs to customers acquired 1–3 months later (choose a lag that matches your typical sales cycle).

- Cohort CAC: attribute the full cost of a cohort's acquisition program to the cohort of customers that resulted.

If you don't correct for lag, you'll mistakenly conclude "CAC spiked" when in reality closes simply slipped into next month.

Step 3: Don't mix "cash" and "P&L" views

CAC is usually a P&L metric (expense incurred), not a cash metric. But founders often care about both:

- P&L CAC helps you understand unit economics.

- Cash timing matters for runway and payback.

If you're paying annual contracts upfront for tools or events, consider whether you amortize those costs for CAC. The key is consistency month to month.

What drives CAC up or down

CAC changes because either costs changed, or conversion/volume changed. In practice, it's usually both.

1) Funnel conversion and sales execution

CAC improves when conversion improves at any stage:

- Higher lead-to-trial or lead-to-demo conversion (see Conversion Rate)

- Higher SQL rate (see SQL (Sales Qualified Lead))

- Higher close rate (see Win Rate)

- Shorter cycle (see Sales Cycle Length)

Even if spend is flat, CAC rises when:

- win rate drops

- sales cycle lengthens (fewer closes per month)

- lead quality declines

Practical diagnostic: if CAC jumped, check whether new customers fell and then trace backward: closed-won → pipeline created → qualified leads → lead volume.

2) Channel saturation and competition

Paid channels often get more expensive as you scale:

- you exhaust the easiest audiences

- competitors bid up the same keywords

- marginal placements convert worse

This shows up as higher CPL (Cost Per Lead) and lower lead-to-customer conversion—double damage to CAC.

3) Pricing and packaging changes

CAC is "cost per customer," not "cost per dollar of revenue," so pricing changes don't directly change CAC. But they can change the quality of customers and the conversion rate:

- Raising price can reduce conversion and increase CAC (fewer customers for same spend)

- Better packaging can increase conversion and reduce CAC

- Heavy discounting can preserve conversion while damaging payback (more on that below)

If you're changing pricing, monitor ASP (Average Selling Price) and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) alongside CAC to avoid false conclusions.

4) Brand, word-of-mouth, and product-led loops

As your product and reputation improve, you often see:

- more direct traffic

- higher conversion from the same traffic

- lower CAC even without spending less

This is why CAC should be interpreted together with retention and satisfaction signals like NPS (Net Promoter Score) and CSAT (Customer Satisfaction Score). Strong retention and advocacy reduce future acquisition pressure.

The Founder's perspective: CAC rarely "improves" because you got better at arithmetic. It improves because you built a stronger acquisition engine: tighter ICP, better positioning, higher conversion, faster sales cycles, or more durable word-of-mouth.

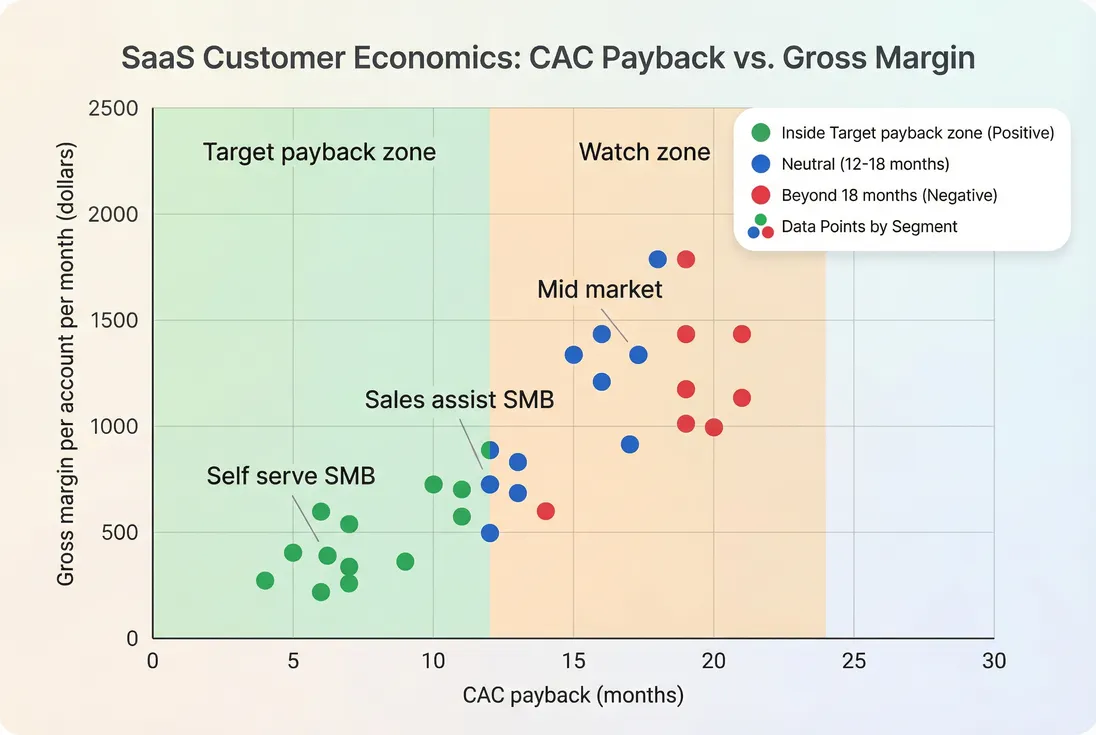

How to tell whether CAC is healthy

CAC has no universal benchmark. A "good" CAC depends on (1) how much gross profit a customer generates per month, and (2) how long they stay and expand.

The three lenses founders should use

1) Payback

Payback answers: how quickly do we earn back CAC from gross profit?

This is usually the first "health" check because it's directly tied to cash efficiency.

- If payback is getting worse, growth is becoming more expensive to finance.

- If payback is improving, you can often scale faster with less risk.

Link this explicitly with CAC Payback Period and Customer Payback Period.

2) LTV relative to CAC

A common unit-economics ratio is:

Use LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and LTV:CAC Ratio as the framework, but don't stop at a single number. Two businesses can have the same LTV:CAC while having very different cash profiles depending on payback speed.

3) Margin and retention reality

CAC is only as "safe" as the retention and margin behind it:

- Falling Gross Margin reduces how much profit is available to pay back CAC.

- Rising Logo Churn reduces realized lifetime and makes CAC riskier.

- Improving NRR (Net Revenue Retention) can justify higher CAC because expansion helps repay acquisition cost.

Practical benchmark ranges (use with caution)

These are broad rules of thumb founders use for orientation, not goals:

| Motion | Typical fully loaded payback | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PLG / self-serve SMB | 3–9 months | Low ACV needs fast payback; watch support and onboarding costs. |

| SMB sales-assist | 6–12 months | Often sensitive to conversion and inside-sales productivity. |

| Mid-market sales-led | 9–18 months | Longer cycles and onboarding can justify slower payback if retention is strong. |

| Enterprise sales-led | 12–24+ months | Evaluate on gross profit, renewal probability, and multi-year expansion path. |

If you're early-stage, stable payback matters more than "perfect" payback. Volatile CAC plus long payback is what creates unpleasant surprises.

How founders use CAC in real decisions

CAC becomes powerful when it informs a specific decision: where to allocate headcount and dollars.

1) Setting growth budgets and hiring plans

If you know your target CAC and payback, you can set a sane acquisition budget:

- If CAC is stable and payback is within target, scaling spend is less risky.

- If CAC is rising and payback is stretching, adding spend often makes the problem worse.

Tie this to cash discipline metrics like Burn Rate and Burn Multiple. A company can "grow" while becoming less capital efficient if CAC is drifting up.

The Founder's perspective: The question isn't "Can we buy growth?" It's "Can we buy growth at a CAC that keeps payback inside our runway?" CAC is a runway management metric as much as a marketing metric.

2) Comparing channels

Channel comparisons fail when:

- costs are tracked by month, but closes happen later

- channels influence each other (content supports paid, brand supports outbound)

- you attribute based on last touch only

A workable founder approach:

- Use paid CAC to optimize channels weekly.

- Use fully loaded CAC to validate that the overall machine is healthy monthly/quarterly.

- If a channel looks "too good," sanity-check: does it still look good when you include the people and tooling required to run it?

3) Pricing and discount policy

CAC interacts with discounting indirectly—but brutally—through payback.

If you discount heavily:

- CAC per customer may stay the same

- gross profit per customer falls

- payback stretches and the business becomes harder to finance

That's why discounting should be evaluated with Discounts in SaaS and with ARPA/ASP trends. If you "save" conversion rate with discounts, you may be quietly trading away unit economics.

4) Segment strategy (SMB vs mid-market)

Blended CAC hides the truth. Segment CAC reveals where you actually have leverage.

Two segments can look like this:

| Segment | CAC | ARPA | Payback risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMB self-serve | Low | Low | Sensitive to churn and support load |

| Mid-market sales-led | High | Higher | Sensitive to cycle length and onboarding cost |

When founders say "CAC is fine," the follow-up is: fine for which segment? Segmenting by plan, industry, ACV, or channel often changes the strategy.

When CAC "breaks" (and what to do)

CAC isn't just a performance score—it's an early warning system. Here are common "break" patterns and the founder actions they call for.

Pattern 1: CAC rises while volume falls

What it usually means

- channel saturation

- messaging mismatch

- lead quality drop

- sales execution regression

What to do

- Diagnose conversion by stage (lead → MQL → SQL → close)

- Review ICP fit and disqualify faster

- Tighten positioning and sales enablement

- Consider reallocating to higher-intent channels

Related metrics to pull in:

Pattern 2: CAC looks stable, but payback gets worse

What it usually means

- price realization dropped (more discounting)

- gross margin fell (higher COGS or support burden)

- churn increased (customers don't stay long enough)

What to do

- Audit discounting and packaging

- Review COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) and Gross Margin

- Look at retention trends with Retention and Cohort Analysis

- Investigate churn drivers with Churn Reason Analysis

Pattern 3: CAC improves "too fast"

What it usually means

- you cut acquisition spend and starved the top of funnel

- you benefited from a short-term channel anomaly

- attribution shifted rather than real efficiency

What to do

- Verify pipeline creation didn't collapse

- Check lagged CAC and next-month closes

- Confirm retention quality didn't deteriorate (cheap customers who churn)

Common mistakes and edge cases

Mistake 1: Counting expansions as "new customer revenue"

CAC is about acquiring new logos. Expansion belongs in retention metrics like Expansion MRR and Net MRR Churn Rate.

Mistake 2: Using signups or trials as the denominator

That turns CAC into something closer to cost per signup, which is not what you need for unit economics. Use leads/trials for funnel optimization, but keep CAC tied to new paying customers.

Mistake 3: Ignoring refunds and chargebacks

Refunds and chargebacks don't change CAC directly, but they can destroy payback and distort "effective acquisition." If refunds are material, review Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS.

Mistake 4: Comparing CAC across months with different definitions

If you changed what's included (tools, payroll allocation, commissions), you changed CAC. Document the change and consider recalculating historical CAC to keep trends comparable.

A simple CAC operating cadence for founders

If you want CAC to drive action (not debates), run it on a cadence:

- Weekly (channel view): paid CAC proxy metrics (lead volume, CPL, conversion rates)

- Monthly (management view): blended paid CAC and fully loaded CAC, with lag adjustment

- Quarterly (strategy view): CAC by segment + payback + retention quality

Pair CAC with:

- ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) to understand revenue per customer

- Logo Churn and NRR (Net Revenue Retention) to validate lifetime value

- Burn Multiple to ensure growth remains capital-efficient

The goal isn't to force CAC down at all costs. The goal is to build an acquisition engine where CAC, payback, and retention align—so you can scale without financing every dollar of growth twice.

Frequently asked questions

CAC is only meaningful relative to payback and retention. A CAC that feels high can be fine if customers stay and expand, and if payback is fast. Evaluate CAC alongside gross margin, churn, and your target payback window. Also check CAC by segment and channel, not just blended.

For decision-making, yes: include sales and marketing payroll, commissions, agency fees, ad spend, and the tools required to acquire customers. You can exclude broad corporate overhead, but be consistent. Many teams track two views: paid CAC for channel optimization and fully loaded CAC for budgeting and runway planning.

CAC rises when the denominator drops. Common causes are lower conversion rates, fewer sales-qualified leads, a longer sales cycle pushing closes into later months, or a shift toward lower-intent channels. Check funnel metrics, pipeline coverage, and close timing. A lag-adjusted CAC view often explains sudden month-to-month spikes.

Discounts usually do not change CAC, but they reduce the revenue and gross profit used to pay CAC back, which can turn a healthy CAC into an unhealthy payback period. Annual prepay improves cash flow and payback timing, but it does not reduce acquisition cost. Track both price realization and CAC together.

Mixing definitions across months or channels. Teams often compare a "paid ads only" CAC in one month to a "fully loaded" CAC in another, or they attribute spend to the wrong period relative to closes. Decide your CAC definition, document it, and use lag or cohort methods so trends reflect reality.