Table of contents

Average sales cycle length

Average sales cycle length quietly determines how "real" your pipeline is. Two companies can show the same qualified pipeline and the same win rate, but the one with a 90-day cycle needs more cash buffer, more pipeline coverage, and more patience than the one with a 21-day cycle. If you ignore cycle length, you'll over-hire, over-forecast, and under-estimate how long it takes revenue to show up.

Average sales cycle length is the average number of days it takes to move a deal from a defined start point (like SQL or opportunity created) to a defined end point (usually closed won), measured across deals closed in a period.

What it measures in practice

Average sales cycle length is a time-to-revenue metric for your sales motion. It answers: how long does a qualified deal take to become a customer?

The metric matters because it directly affects:

- Forecasting accuracy: revenue shows up with a lag equal to your cycle length.

- Capital planning: long cycles delay cash and increase the burn required to grow (see Burn Rate and Burn Multiple).

- Sales capacity: longer cycles mean reps can actively progress fewer deals at once.

- Go-to-market fit: cycle length often expands when you move upmarket or sell into regulated industries.

It's also a diagnostic tool. When cycle length rises, deals are either:

- entering the pipeline less qualified,

- getting stuck in one specific stage (security, procurement, integration), or

- facing increased "hidden work" like custom terms, extra stakeholders, or pricing approvals.

The Founder's perspective

If average cycle length increases and you keep hiring based on last quarter's close rate, you'll feel it as missed forecasts and mounting pressure to discount. This metric is often the earliest sign that your go-to-market motion is changing faster than your team realizes.

How to calculate it reliably

At its simplest, you measure the day difference between start and end for each closed-won deal, then average.

Choose start and end points

This is where most teams create inconsistent numbers. Pick definitions that match your sales reality.

Common start points (pick one):

- SQL date (best when marketing-driven nurture time varies)

- Opportunity created date (best when pipeline hygiene is strong)

- First meeting date (best when outbound can create early opportunities)

Common end points (pick one):

- Closed won date in CRM (best for consistent reporting)

- Contract signed date (best if signature precedes payment by weeks)

- First invoice paid date (best if cash timing is the priority)

Practical guidance: if you're managing bookings and forecasting, "closed won" is usually the cleanest end point. If you're managing cash and collections, also look at Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging and Deferred Revenue.

Use averages, but don't trust them alone

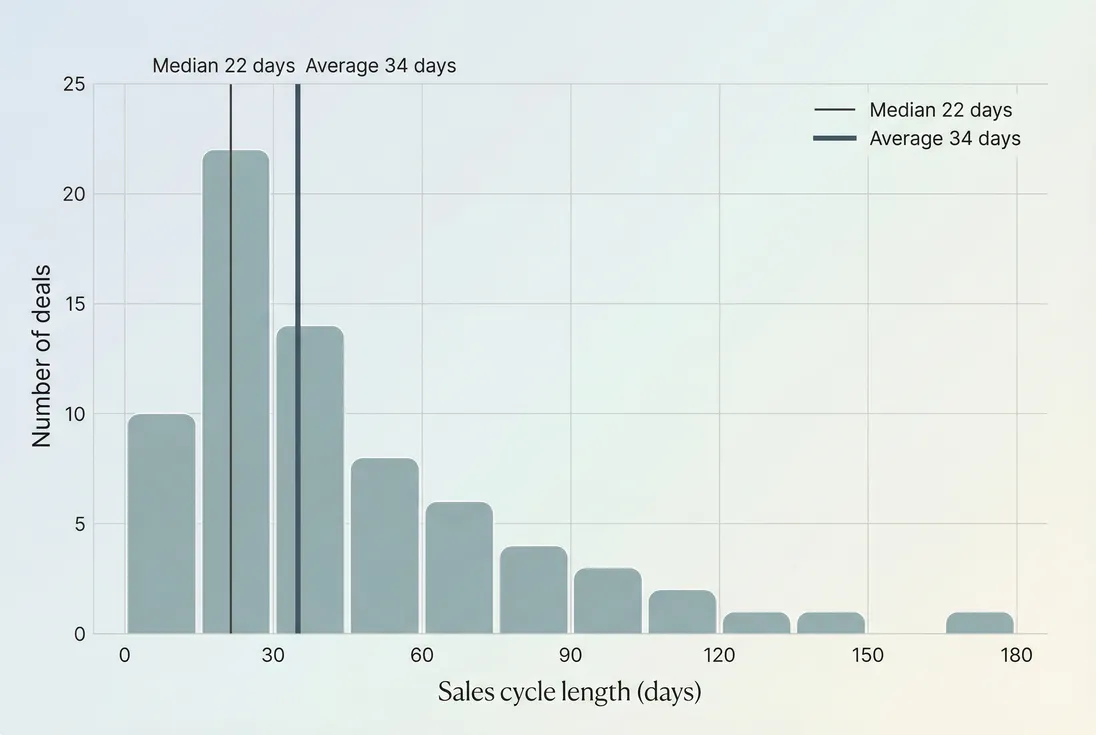

Sales cycle distributions are rarely normal. A few "enterprise whales" can distort the average and make your motion look slower than it is for most deals.

Track these together:

- Average cycle length (sensitive to long tail)

- Median cycle length (typical experience)

- Percentiles (like 75th or 90th) to quantify the long tail

Averages drift upward when a few deals take much longer; pairing average with median prevents you from optimizing for outliers.

Segment before you conclude anything

Overall average cycle length is often a misleading blend of different motions. Segment by factors that change buyer behavior:

- ACV / pricing tier (see ACV (Annual Contract Value) and ASP (Average Selling Price))

- Customer size or industry

- Inbound vs outbound

- Self-serve vs sales-assisted

- New business vs expansion (expansion cycles are usually shorter, and tie directly to Expansion MRR)

A simple rule: if you changed what you sell (bigger contracts), who you sell to (more regulated buyers), or how you sell (more steps), you must segment or the metric will lie.

Avoid weighting mistakes

By default, this metric is deal-weighted (each deal counts equally). That's usually what you want for process diagnosis.

Sometimes you also want revenue-weighted cycle length to understand how quickly dollars close (useful for ARR planning):

Use it carefully: it will heavily reflect enterprise deals and can make a healthy SMB motion look irrelevant.

What drives it up or down

Average sales cycle length is the outcome of many small frictions. For founders, the goal isn't to force the number down—it's to understand which frictions are worth removing and which are inherent to your market.

Buyer complexity and stakeholders

Cycle length increases when:

- The buyer needs multiple approvals (manager, finance, security, legal, procurement).

- The buyer demands a business case or ROI model.

- There's an incumbent tool and a competitive bake-off.

This is why moving upmarket often increases cycle length even if your product is better.

Process steps you control

Cycle length decreases when:

- Qualification is sharper (fewer "maybe" deals entering pipeline). Pair with Qualified Pipeline and Win Rate.

- You reduce time between steps (faster follow-up, tighter next-step scheduling).

- The demo-to-trial or demo-to-pilot path is standardized.

- You remove custom terms, custom pricing, and one-off redlines as the default.

Product and implementation risk

Buyers delay decisions when the cost of a bad decision is high. Common causes:

- Complex integrations

- Data migration uncertainty

- Security posture unclear

- Need for internal enablement and training

This is where product and sales ops meet. A "slow sales cycle problem" can actually be a packaging problem, implementation problem, or trust problem.

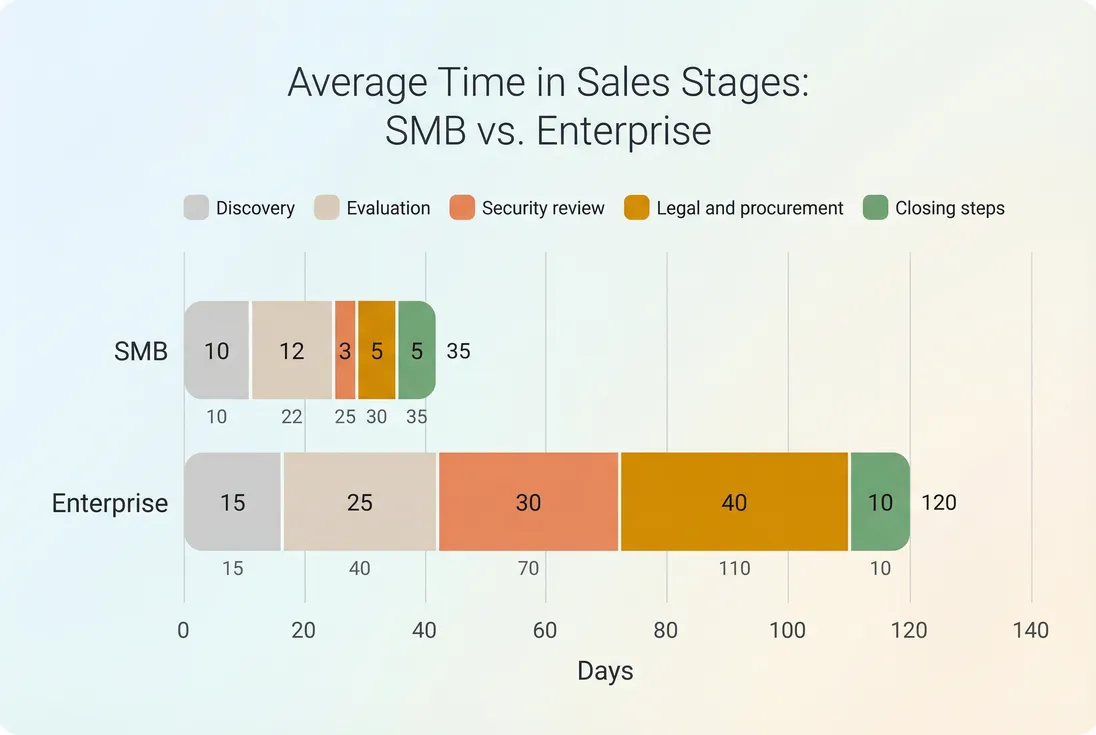

Stage-level bottlenecks matter more than the average

If you want to improve cycle length, don't obsess over the final number. Break the cycle into stage durations and find the single biggest delay.

Stage-level timing shows where cycle length is created; enterprise cycles are often dominated by security and procurement, not selling.

How founders should interpret changes

The most useful question isn't "is the cycle long?" It's: what changed, and is that change good or bad?

When a longer cycle is healthy

Cycle length rising can be a positive signal if it comes with:

- Higher ACV / ASP (see ASP (Average Selling Price))

- Higher win rate in a better ICP

- Better retention outcomes later (track NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention))

Example: shifting from $3k ACV to $25k ACV may take you from 14 days to 55 days. That's not a problem if your unit economics improve (see LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost)).

When a longer cycle is a warning

Cycle length rising is concerning when it pairs with:

- Flat or declining win rate

- Increasing discounts (see Discounts in SaaS)

- More deals sitting in late stages

- Lower pipeline velocity (see Lead Velocity Rate (LVR))

This combination usually means your pipeline is less qualified or your sales steps have become heavier without an ACV payoff.

The Founder's perspective

I treat a cycle-length spike like a product incident: it deserves a root-cause review within a week. If you wait a quarter, the feedback loop is too slow and you'll "fix" it with discounting—hurting both ASP and retention.

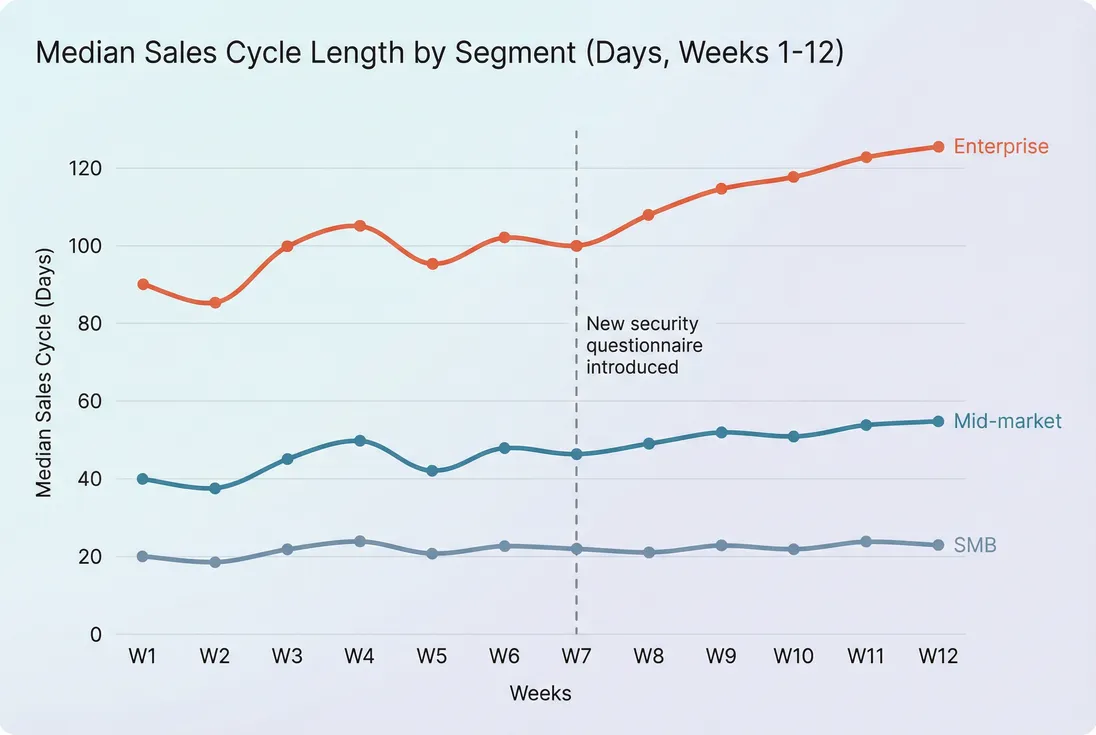

Look for mix shift versus true slowdown

A common trap: you add enterprise deals and the overall average jumps. That may simply be mix shift.

To tell the difference:

- Check cycle length within the same ACV bands.

- Compare new pipeline composition by segment.

- Track stage conversion rates: if stage-to-stage conversion worsens, you likely have a real slowdown.

A practical workflow:

- Split deals into ACV buckets (e.g., under 5k, 5k to 25k, 25k plus).

- Track average and median for each bucket.

- Only treat it as a problem if buckets themselves worsen.

Watch the long tail

Most forecast misses come from the long tail: deals that "should have" closed but didn't.

Operationally, watch:

- Share of deals older than 2 times your median cycle

- Late-stage aging (especially "legal/procurement" and "final review")

If that tail grows, your average will creep up and your forecast will slip—even if the median looks stable.

Trend cycle length by segment; a process change can slow enterprise deals without affecting SMB, which is invisible in blended averages.

How founders use it to make decisions

Average sales cycle length becomes powerful when you connect it to planning: revenue timing, hiring, and cash needs.

Forecasting with realistic timing

If your average cycle is 60 days, pipeline created this month mostly impacts bookings two months from now. That sounds obvious, but many forecasts implicitly assume near-instant conversion.

Use cycle length to:

- Lag your expectations (don't forecast Q1 pipeline as Q1 revenue unless your cycle supports it).

- Set realistic targets for pipeline coverage and time-to-close by segment.

- Explain variance: "we missed because enterprise cycle expanded from 85 to 105 days after adding security steps."

Cycle length also affects the interpretation of Qualified Pipeline. A large pipeline is less valuable if it takes much longer to convert.

Hiring and capacity planning

Longer cycles reduce how many active deals a rep can progress without quality dropping.

If cycle length rises and you respond by hiring, you may mask the real issue (process friction) with headcount, which increases burn. Before adding reps, ask:

- Is cycle length rising in a specific stage (procurement, security)?

- Did we start selling a more complex product configuration?

- Are we entering deals earlier (worse qualification) to "hit pipeline goals"?

Tie this back to Sales Rep Productivity and Sales Efficiency. If productivity falls while cycle length rises, the bottleneck is likely operational, not effort.

Unit economics and payback

Sales cycle length increases the time between spending CAC and realizing revenue. It doesn't change CAC itself, but it extends payback and raises working-capital needs.

If you're managing to a specific payback target, connect cycle length to CAC Payback Period. A longer sales cycle often means:

- More months of payroll and tooling before a deal closes

- More pressure to pull forward results (often via discounting)

Discounting can shorten cycles, but it can also create longer-term problems:

- Lower ASP reduces the upside of long-cycle deals

- Discount-driven closes often churn sooner (watch Logo Churn and Customer Churn Rate)

The Founder's perspective

If you have to discount to keep the cycle from getting longer, you're paying to hide a bottleneck. I'd rather accept a slower quarter and fix the stage friction than permanently lower ASP and train buyers to wait you out.

Packaging and go-to-market choices

Cycle length is one of the clearest signals to decide whether to:

- Double down on SMB/PLG

- Build a mid-market sales-assist motion

- Commit to enterprise (and accept the procurement and security realities)

If you're considering a move upmarket, forecast what happens if:

- Cycle length doubles

- Win rate drops temporarily during learning

- ASP increases

That combination can still be net-positive, but only if you plan runway and pipeline accordingly (see Runway and Capital Efficiency).

Practical benchmarks founders use

Benchmarks are rough, but they help you sanity check your expectations. Use these as starting points, then calibrate to your ICP and your own historical baseline.

| Segment / motion | Typical cycle length range | What usually drives it |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve SMB | 0–14 days | Trial time, onboarding friction, pricing clarity |

| Sales-assisted SMB | 14–45 days | Scheduling, basic stakeholder alignment, light procurement |

| Mid-market | 30–90 days | Multi-stakeholder evaluation, security review, integrations |

| Enterprise | 90–180+ days | Security, legal, procurement, budget cycles, pilots |

A healthy improvement target is usually 10–20% reduction within a segment over a quarter—assuming you're removing specific frictions, not just pushing harder.

Common pitfalls that make the metric useless

Mixing deal types

Don't blend these without segmentation:

- New business vs expansions

- One-seat "team" plans vs platform purchases

- Partner-led vs direct

- Regions with different procurement norms

If you must report one number, report the blended number plus segment medians so leadership can interpret it correctly.

Measuring from the wrong start date

Using "lead created" can turn marketing nurture time into "sales cycle length," making the number swing with campaign mix rather than sales performance.

If you need to include pre-SQL time, track it separately as lead-to-SQL or lead-to-opportunity time (see Lead Conversion Rate and SQL (Sales Qualified Lead)).

Excluding lost deals entirely

Average sales cycle length is usually calculated on closed-won deals, but you should also look at:

- Average time-to-loss

- Where losses happen (early vs late)

If losses are happening late, your cycle can look "efficient" because only the fastest wins remain in the data—while your team wastes time on deals that never close. This pairs well with Churn Reason Analysis style thinking, but applied to pipeline: why deals stall and die.

Bad CRM hygiene

The metric breaks when:

- Opportunities are created long after the first meeting

- Close dates are constantly pushed out but not tracked

- Deals are reopened without a new start definition

If you can't trust the timestamps, you'll "optimize" the wrong thing.

How to reduce sales cycle length without discounting

Cycle length reduction is mostly about removing uncertainty and compressing gaps between steps.

Start with a simple approach:

- Find the slowest stage (stage duration, not just the overall cycle).

- Identify the cause (security questions, unclear ROI, missing integration details).

- Create a default asset or process (security packet, ROI template, implementation plan).

- Tighten next steps (always leave meetings with a scheduled calendar event).

Tactics that consistently work in SaaS:

- Standardize security and compliance responses (one source of truth).

- Offer a tightly scoped pilot with clear success criteria and a deadline.

- Create a "mutual close plan" for deals above a threshold ACV.

- Simplify pricing and approval paths (fewer bespoke discounts).

- Improve onboarding and time-to-value for sales-assisted customers (see Time to Value (TTV)).

The bottom line

Average sales cycle length is a timing metric with strategic implications. It tells you how quickly pipeline becomes ARR, how much cash buffer you need, and where your go-to-market motion is getting heavier.

Use it correctly by:

- Defining consistent start/end points

- Pairing average with median and percentiles

- Segmenting by ACV and motion

- Breaking it down by stage to find the real bottleneck

When the number changes, don't react with pressure and discounts. Diagnose whether it's mix shift, process friction, or product risk—and then fix the part that actually changed.

Frequently asked questions

Good depends on your deal size, buyer, and process complexity. A 14 day cycle can be slow for self serve SMB, but extremely fast for enterprise. Use your own baseline first, then segment by ACV and channel. If cycle length is rising while win rate is flat, something is slowing decisions.

Track both. The average is useful for capacity planning because long deals consume real sales time, but it gets distorted by a few very slow deals. The median shows what a typical deal experiences. If average rises but median stays flat, you likely have a handful of stuck deals.

Pick a start event that reflects real selling work and keep it consistent. Common choices are SQL date, first meeting date, or opportunity created date. Avoid lead created if marketing generates long nurture periods. The end date is usually closed won date or contract signature date, not first payment.

Larger buyers add steps: security review, legal redlines, procurement, and more stakeholders. Your average can jump even if your process is healthy. Segment by ACV and buyer type to confirm. Then reduce friction with standard security docs, tighter pilot scopes, and pricing and terms that require fewer approvals.

Longer cycles delay bookings and cash, so you need more pipeline coverage and more runway to hit the same ARR plan. Before hiring more reps, verify whether the constraint is lead volume, win rate, or cycle time. A 30 percent longer cycle often requires meaningfully more pipeline to maintain growth.